“I’m not a real person. I’m a legend.”

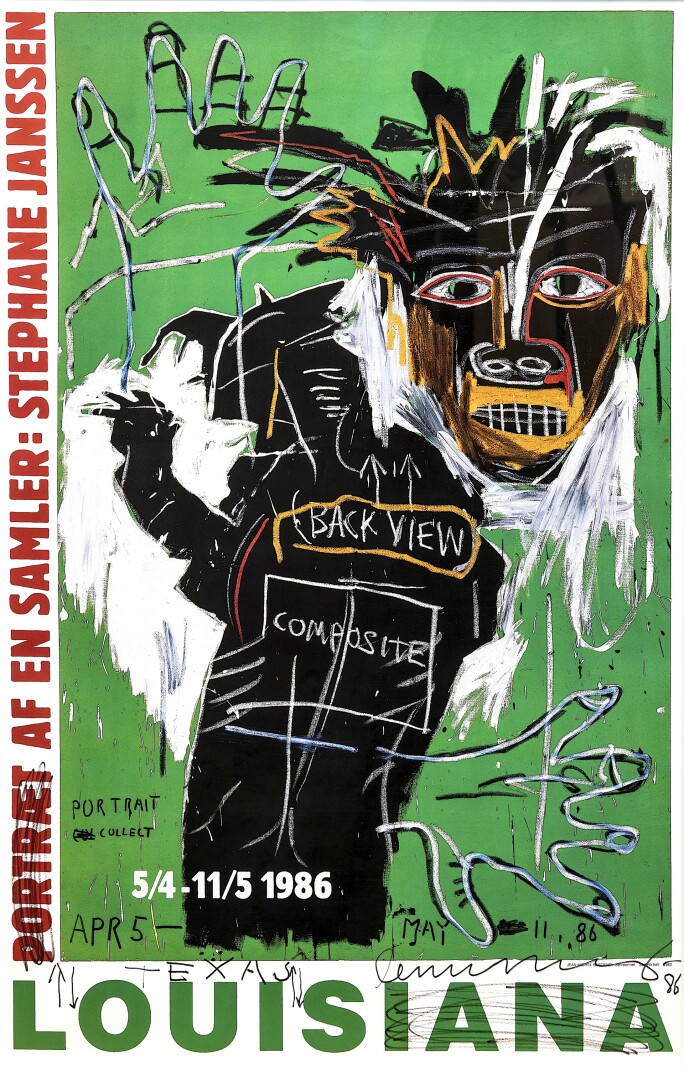

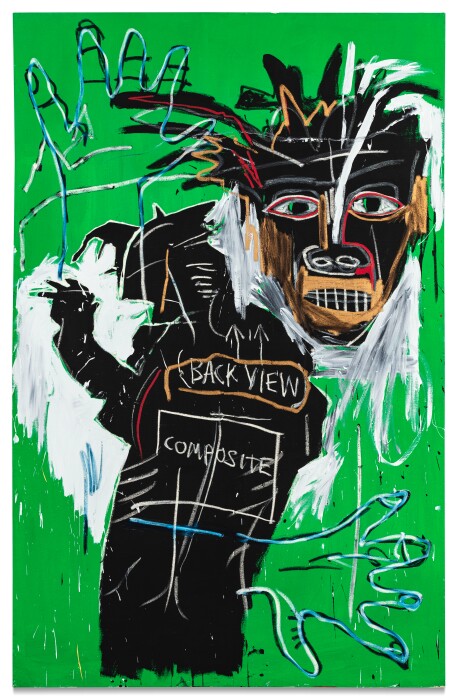

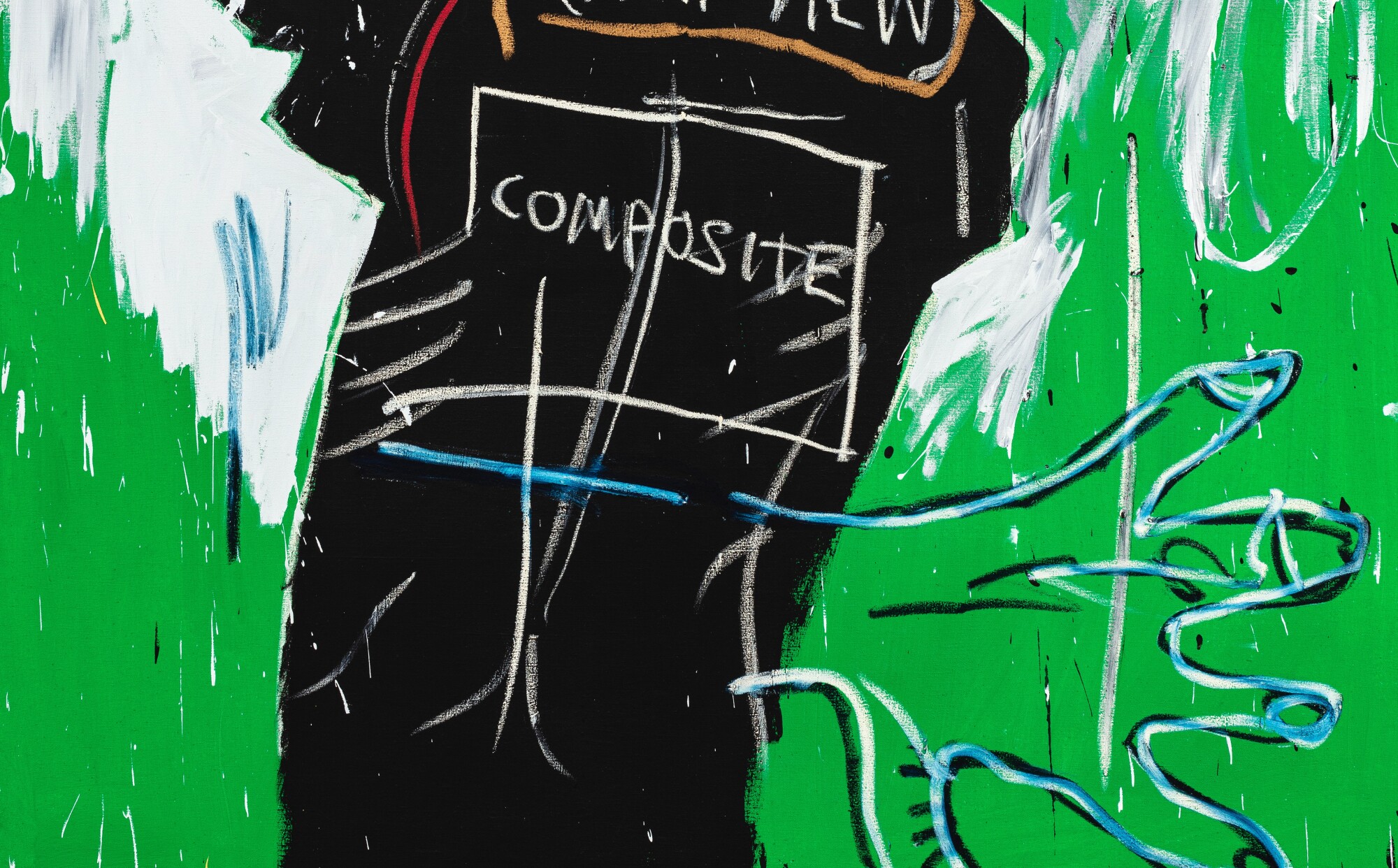

Amidst a cacophony of fragmented body parts upon a luminescent green field, Basquiat's collective image emerges piece by piece in his monumental Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part Two), wholly enveloping the viewer with the artist’s profound understanding of selfhood at the pinnacle of his brief but explosive career. By the time Basquiat painted the present work in 1982, he had already arrived at the center of critical acclaim as he ascended from SAMO ©, the street provocateur, to the avant garde prodigy of the mainstream art world. Emerging from the downtown crucible of his native New York, Basquiat executed Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part Two) during a pivotal visit to Los Angeles between 1982 and 1983, a critical turning point in his life when he debuted in his first West Coast exhibitions at Larry Gagosian Gallery and prominently featured the present work therein. Alongside Versus Medici and Anybody Speaking Words, the present work was originally one of several monumental standing Black figure paintings that formed the core of esteemed Belgian collector Stéphane Janssen’s collection – an esteemed Belgian collector and an early champion of Basquiat – and is distinguished today as among the artist’s most assured, early masterworks. Its sister painting, the first Self-Portrait as a Heel from 1982, similarly depicts a stylized rendering of the artist’s own head with swirling dreadlocks; meanwhile, the overall titular motif remained significant for the artist, notably continuing in an inscription “Self-Portrait as a Heel, Part Three” that is scribbled alongside a portrait of himself and two friends – Toxic and Rammellzee – in his later 1983 painting Hollywood Africans, now held in the Whitney Museum of American Art as an autobiographical depiction of his legendary experience in Los Angeles. A majestically viridescent monument to the inseparability between Basquiat’s art and his own life as a Black American man, Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part Two) powerfully reflects one of the artist’s most powerful and philosophical rendition of the self as, in his words here, a “COMPOSITE” – not only of who he understands himself to be, but also what others will inevitably perceive and identify him as.

"['Heel' may be] a self-deprecating description of himself as a ‘cad’ or ‘jerk,’ perhaps commenting on his behavior with friends, dealers, or girlfriends, and secondly, he enjoyed the act of labeling something a HEEL, in the same way he labeled parts of the body in his anatomical works.”

More so than depictions of himself, Basquiat’s self-portraits during the 1980s serve as nuanced portrayals of his self-consciousness as he navigated the white, Western artistic continuum: by representing himself from the “BACK VIEW” in Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part Two), Basquiat unmistakably presents an onlooker’s perspective of him while avoiding our direct gaze. Emerging with a halo of flurried white brushstrokes yet cast in the stark umbra of shadow, the artist’s black silhouette seems to lurk in sinister darkness, providing a counterpart to his disembodied head as it vigorously confronts us with contours resembling an African tribal mask and his signature crown of dreadlocks. In this context, the titular “heel” references not only the back of a shoe, but also the pejorative used to indicate a delinquent, or the boxing term for a professional wrestler who acts as the antagonist within a match, the foil to the boxer cast as the hero. Regarding Basquiat’s multivalent application of the word “heel”, Richard Marshall interprets it as “a self-deprecating description of himself as a ‘cad’ or ‘jerk,’ perhaps commenting on his behavior with friends, dealers, or girlfriends, and secondly, he enjoyed the act of labeling something a HEEL, in the same way he labeled parts of the body in his anatomical works.” (Richard D. Marshall and Jean-Louis Prat, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1st. Ed., vol. I, Paris, 1996, p. 20). Lending his pithy poeticism to the canonical mode of self-portraiture, Basquiat allegorizes the dualities of his selfhood through the opposition between the “heel” and hero, and he contends with the cultural stereotypes and alienation that he encountered as a young Black man in Twentieth-Century America.

'Many iconographic traditions were legitimately his to manipulate and explore, as were Gray’s Anatomy, or Leonardo’s; or the hobo symbols he found in Henry Dreyfus’s Symbol Sourcebook. In a democratic and free universe, all cultures and all information belonged to him as consumer of knowledge and producer of cultural artifacts.”

Ever the iconographic alchemist, Basquiat compounds in Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part II) an extraordinary exploration of corporeality grounded in familiar anatomical illustrations, aesthetic ballast for his expansion of the self-portraiture tradition that is executed with unprecedented intensity in the present work. Basquiat’s obsession with the architecture of the body originates from a pivotal incident in the artist’s childhood when, after being struck by a car, the young Jean-Michel was hospitalized for a broken arm. It was during this time that the artist’s mother gave him a copy of the seminal medical tomb Gray’s Anatomy, an anecdotal genesis that would inform the present work, among others of Basquiat’s most ravishing, diagrammatically incisive paintings. Describing the manner in which Basquiat freely remixed and freshly articulated the signs and symbols of the book, Marc Mayer remarks, “Many iconographic traditions were legitimately his to manipulate and explore, as were Gray’s Anatomy, or Leonardo’s; or the hobo symbols he found in Henry Dreyfus’s Symbol Sourcebook. In a democratic and free universe, all cultures and all information belonged to him as consumer of knowledge and producer of cultural artifacts.” (Marc Mayer, “Basquiat in History,” in Exh. Cat., New York, Brooklyn Museum (and travelling), Jean-Michel Basquiat, 2005, p. 52) With the searing physicality of his frenzied brushstrokes and furiously scrawled forms, Basquiat anchors Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part II) in the tangible realm, as though to adamantly reaffirm his own Black bodily presence within the tenuous melee of his self-identity.

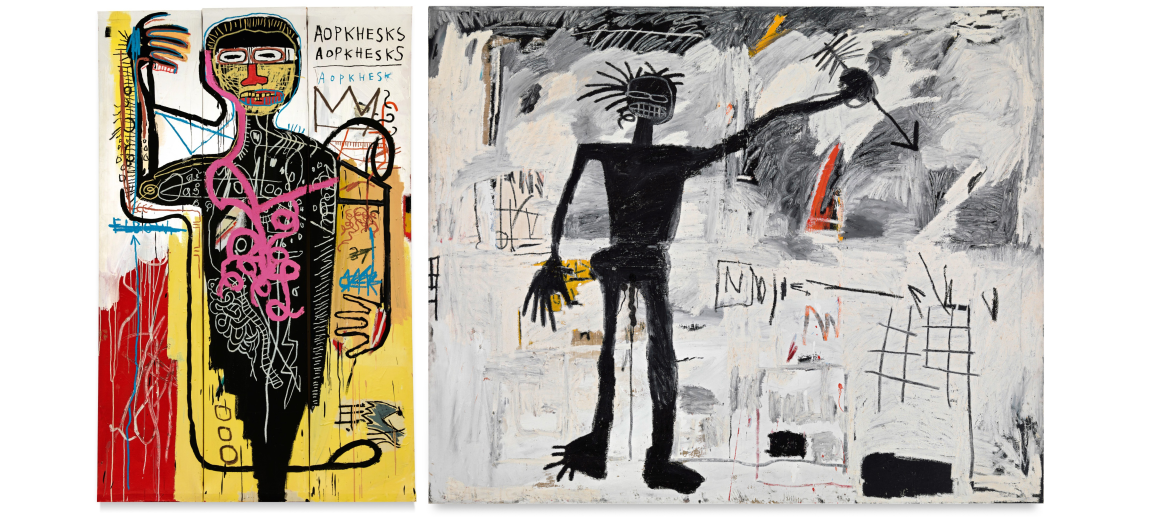

Self Portrait as a Heel (Part II) is among the most iconic paintings that Basquiat titled as “self-portrait,” with its sister painting, the first Self Portrait as a Heel from 1982, similarly depicting a stylized rendering of the artist’s own head with swirling dreadlocks.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Self Portrait as a Heel (Part 1), 1982. Private Collection Bridgeman Images Like many of Basquiat’s best-known portraits, his image in the present work is not of flesh, but of shadow. Superimposed with hieroglyphic-like words, “BACK VIEW” and “COMPOSITE,” Basquiat’s totemic silhouette embodies the haunting specter of darkness, a visual metaphor for the radical self-consciousness of existing as a Black man in contemporary America.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Back of the Neck, 1983. Brooklyn Museum. Basquiat’s disembodied head vigorously confronts us with contours resembling an African tribal mask as well as his signature crown of dreadlocks.

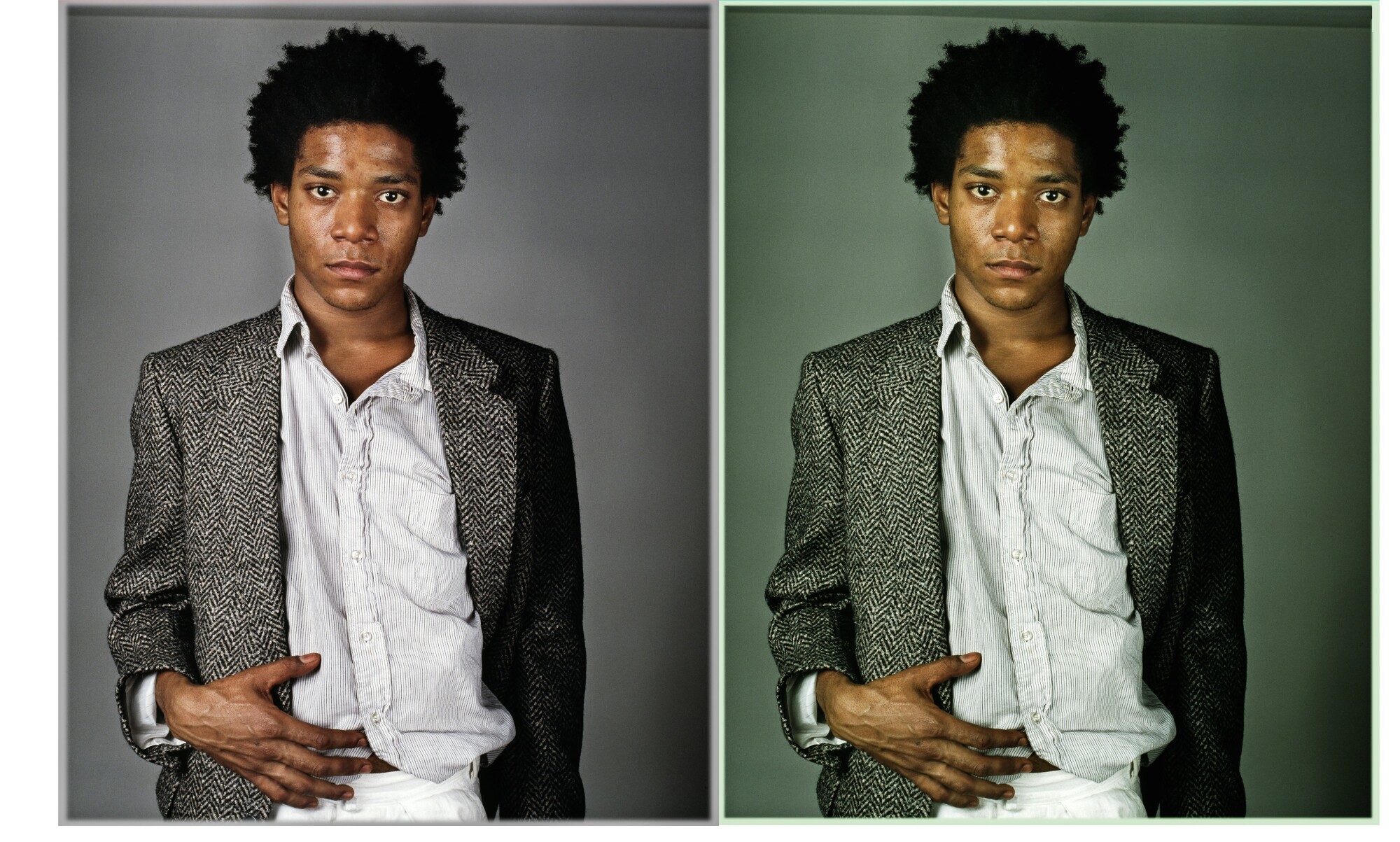

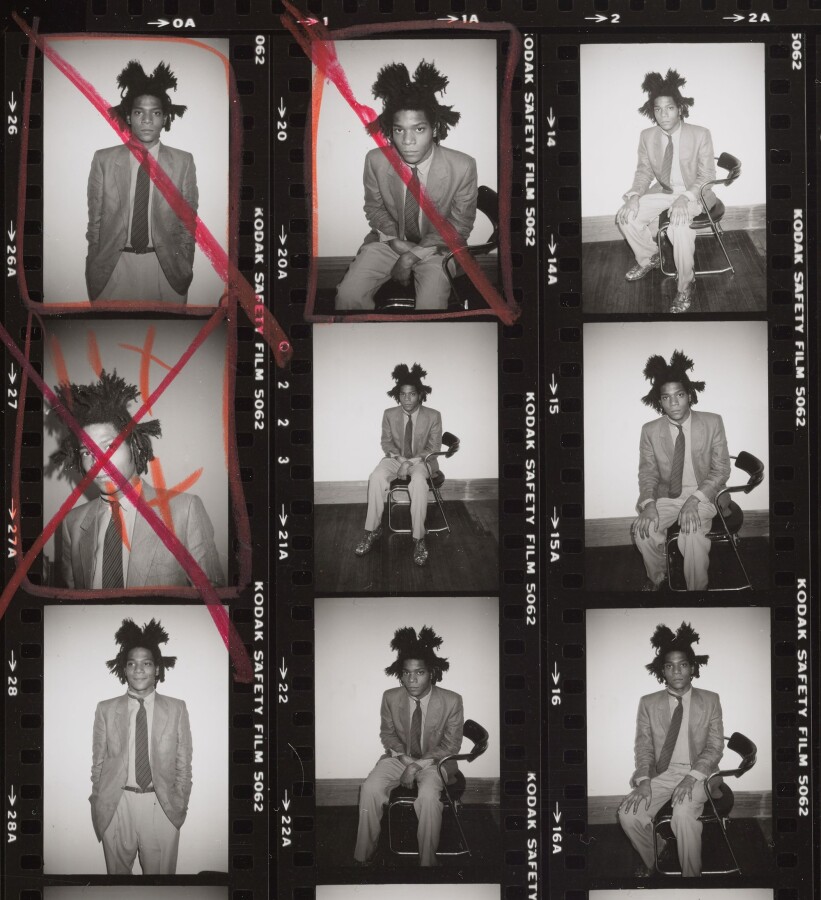

Left: Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1982.

Right: Dan mask, Dr. Werner

The titular “heel” references not only the back of a shoe, but the boxing term for a wrestler who acts as the antagonist within a match, or the pejorative used to indicate a delinquent. Regarding Basquiat’s multivalent application of the word “heel”, Richard Marshall interprets it as “a self-deprecating description of himself as a ‘cad’ or ‘jerk,’ perhaps commenting on his behavior with friends, dealers, or girlfriends.

Paddy DeMarco and Jimmy Carter, 1954. Bettmann / Contributor via Getty Images Bettmann/Bettmann Archive Gifted to him at an early age by his mother, the seminal medical tomb Gray’s Anatomy informs the anatomical drawings of present work among others of Basquiat’s most ravishing, diagrammatically incisive paintings.

Skeletal hand illustration from Gray’s Anatomy, 1893. The present work achieves a mastery of color and form through gestural brushstrokes which reference the kinetic compositions of the Abstract Expressionists. Here, Basquiat emerges from rich marks of white which strengthen and enforce his silhouetted body and head.

Willem de Kooning, Door to the River, 1960. Image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY. Art © © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

"In Basquiat’s work, flesh on the black body is almost always falling away... Stripping away surfaces, Basquiat confronts us with the naked black image. There is no ‘fleshy’ black body to exploit in his work, for that body is diminished, vanishing."

Basquiat’s portrait in the present work is not of flesh, but of shadow. Superimposed with hieroglyphic-like words, “BACK VIEW” and “COMPOSITE,” and labeled enigmatically as a “heel,” Basquiat’s totemic silhouette embodies the haunting specter of darkness, a visual metaphor for the radical self-consciousness of existing as a Black man in contemporary America. “In Basquiat’s work, flesh on the black body is almost always falling away. Like skeletal figures in the Australian aboriginal bark painting…, these figures have been worked down to the bone,” writes the late Black theorist bell hooks. “Stripping away surfaces, Basquiat confronts us with the naked black image. There is no ‘fleshy’ black body to exploit in his work, for that body is diminished, vanishing” (bell hooks, “From the Archives: Altars of Sacrifice, Re-membering Basquiat,” Art in America, 1 June 1993 (online)).

“The analogy between a mirror and the picture plane is rendered explicit in Self-Portrait as a Heel, Part Two (1982), which turns the trope into a perceptual puzzle… The self-portrait merely translates the artist’s permanent state of self-alienation into concrete visual terms. Basquiat always looked back at himself – as well as us – from the place of the Other. This is what, for all its exuberance and generosity, is ultimately so austere about his project.”

In Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part II), Basquiat visualizes this very disintegration in the corporeal mechanism of his own Black body: his fingers are outstretched, his hands severed and fragmented, and, for all its graphic potency, his body and mask-like head zoom into focus only from the ghostly erasure of a whitewashed void. Back to back, the shamanistic forms of Basquiat’s image invoke at once the primitive ritualism of Voodoo totems and the dry academic rigor of science textbooks. Paralleling Basquiat’s spectacular rise in the white-dominated arena of postmodern art during the 1980s, every expressive mark and symbol that constructs such self-imagery in Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part II) expresses the undying spirit of an artist – one whose own ambition was filtered through a profound ambivalence towards the world that lauded him with meteoric success.

Enveloping his split image with an ambiance as surreal and mystifying as his phenomenology of the self, the vibrant green of the present field paints a beguiling stage for this narrative unfolding. In this viridescent field, Basquiat ignites his blackened figure with blazing strands of scarlet and goldenrod, reflecting the Pan-African colors that Basquiat would increasingly absorb into his palette beginning in the 1980s. As Marc Mayer notes, "With direct and theatrically ham-fisted brushwork, he used unmixed color structurally, like a seasoned abstractionist, but in the service of a figurative and narrative agenda. Basquiat deployed his color architecturally, at times like so much tinted mortar to bind a composition, at other times like opaque plaster to embody it. Color holds his pictures together, and through it they command a room." (Marc Mayer, Op. Cit., p. 46) Just as much as Basquiat’s emerald palette utterly seizes the viewer’s attention, however, his “paintings turn back on us, too,” writes scholar Dick Hebdige about the present work. “The analogy between a mirror and the picture plane is rendered explicit in Self-Portrait as a Heel, Part Two (1982), which turns the trope into a perceptual puzzle. A representation of Basquiat’s face and hands is clearly visible, pressed against ‘glass’ as if trying to escape in one direction, while the words ‘BACK VIEW’ and ‘COMPOSITE’ are posted on the back of the same figure which is fleeing in the other direction… The self-portrait merely translates the artist’s permanent state of self-alienation into concrete visual terms. Basquiat always looked back at himself – as well as us – from the place of the Other. This is what, for all its exuberance and generosity, is ultimately so austere about his project.” (Dick Hebdige, “Welcome to the Terrordome: Jean-Michel Basquiat’s ‘Dark’ Side of Hybridity,” in Exh. Cat., Jean-Michel Basquiat, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (and travelling), October 1992-January 1994, p. 61)

“I knew he was great—he was electric. A tesla coil with dreadlocks—cool fire emanating wherever he went. Magic.”

Gazing outward while simultaneously performing an inward examination, Basquiat lays bare the dialectical construction of public and private selves, while his hand sketches leave behind traceries of his struggle to grasp his own composition. Unfurled across the vibrant jade field, in Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part II), he scatters fragmented pieces of himself like entrails — raw, unconcealed, exuding a palpable sense of confidence and vulnerability at once. Ego, id, and superego subsequently collapse into a raw painterly manifesto of the self in this relic from the absolute apex of Basquiat’s career in 1982, testifying to the transcendental breakthrough that is the artist’s indelible legacy. “I knew he was great—he was electric,” recalls Glenn O’Brienn about the late artist. “A tesla coil with dreadlocks—cool fire emanating wherever he went. Magic.” (Glenn O’Brien, “Basquiat: The Show Must Go On,” 17 September 2013 (online)) Nowhere is this visceral sense of magic best exerted than in Self-Portrait as a Heel (Part II), a lustrous masterpiece of mystifying emerald green splintered into the philosophical throughlines of Basquiat’s selfhood, yet illuminated and enchanted with the seismic force of the artist’s gestural bravado. In this painterly battleground whereby Basquiat examines and poignantly reflects upon the precarity of own Black selfhood, he reifies one of his most iconic proclamations: “I’m not a real person. I’m a legend” (Jean-Michel Basquiat quoted in Anthony Haden-Guest, “Burning Out”, Vanity Fair, November 1988, p. 197 (online)).