“It is [Jacqueline’s] image that permeates Picasso’s work from 1954 until his death, twice as long as any of her predecessors […] It is her body that we are able to explore more exhaustively and more intimately than any other body in the history of art… And lastly it is her vulnerability that gives a new intensity to the combination of cruelty and tenderness that endows Picasso’s paintings of women with their pathos and their strength.”

Nu assis dans un fauteuil belongs to a series of canvases on the theme of seated female nude Picasso executed in late 1964 – early 1965 at Notre-Dame-de-Vie, the home in Mougins which Picasso acquired as a gift for Jacqueline Roque shortly after their marriage in 1961. Bursting with colour and exuberant energy, this work bears witness to the extraordinary creative urge that characterised Picasso’s mature work. It is also testament to the renewed sense of joy and fulfillment that Jacqueline’s presence brought to the last seventeen years of Picasso’s life.

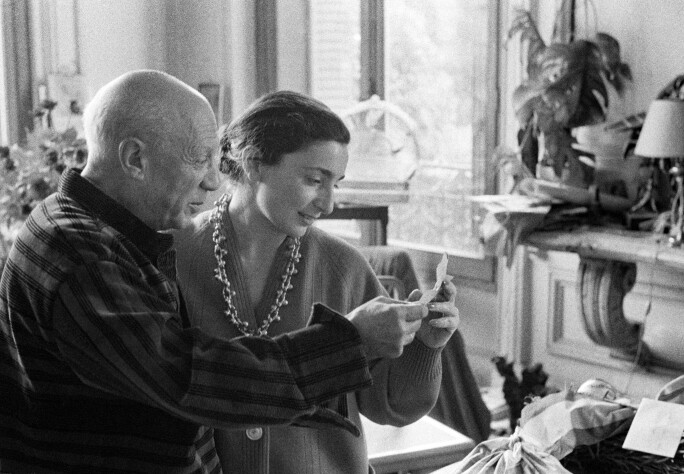

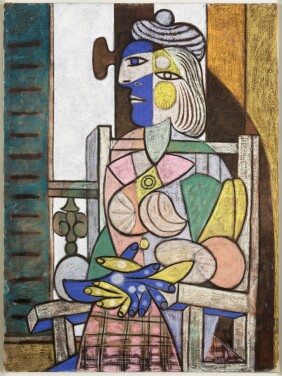

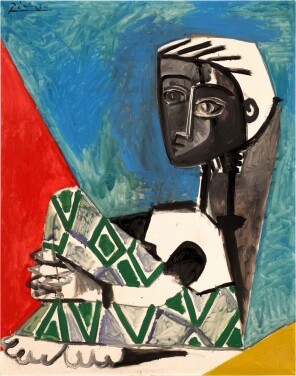

The regal female nude enthroned in an armchair and wearing a crown-like headpiece at the centre of the present composition is, as in the majority of his late portraits, inspired by Jacqueline’s ever-present figure. Picasso’s representations of Jacqueline constitute the largest group of images of any of the women in his life, and these final years of his career have been fittingly termed “l’époque Jacqueline”. The couple first met in 1952 at the pottery studio in Vallauris, where Picasso was working on his ceramics, while he was still living with the mother of his two children, Françoise Gilot. By 1954, Françoise had left, and Jacqueline’s unmistakable angular profile, dark, spirited eyes and raven black hair began to appear in Picasso’s paintings. Although Jacqueline reportedly never posed for the artist, her timeless beauty – which he believed embodied any woman and all women – served as a perfect genesis for Picasso's incessant exploration of the numerous modes from throughout the artistic canon.

With her upright, stoic pose and piercing, enigmatic gaze, Jacqueline emerges here as an ancient deity-like figure imbued with primal feminine energy. The use of brightly saturated red, orange, pink and turquoise hues, coupled with the broad, vigorously applied, rhythmic brushstrokes result in a composition of wonderful rawness and vitality. Picasso further intensifies the solid power exuded by the seated figure by introducing strong verticals and horizontals that frame her within the composition. As Richardson aptly notes on Picasso’s works from this period, “The surface of the late paintings has a freedom, a plasticity, that was never there before; they are more spontaneous, more expressive, and more instinctive than virtually all his previous work” (J. Richardson in Exh. Cat., London, Tate, Late Picasso,1988, pp. 31-34).

Conceptually, Nu assis dans un fauteuil can be viewed as an evolution from the canvases exploring the subject of the painter and his model which preoccupied Picasso’s imagination throughout the early 1960s and which, towards 1963-64, became an almost singular focus of his attention (fig. 2).

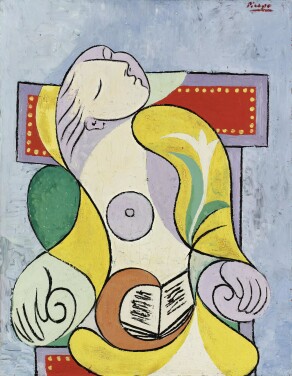

Shortly thereafter, Picasso began isolating first the figure of the painter (fig. 3) and subsequently, the model, producing a series of rapidly executed canvases throughout 1964 which depicted the female figure in a predominantly reclined pose, often leaning against cushions (fig. 4).

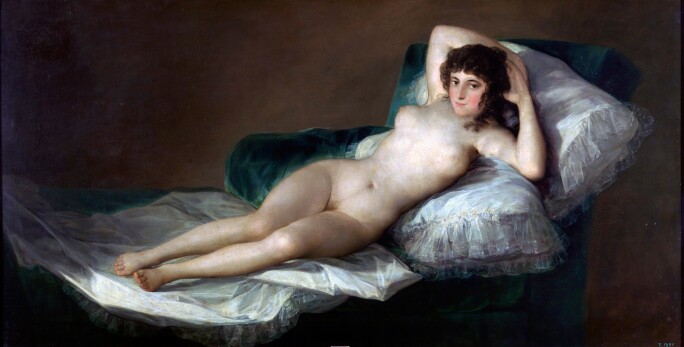

In his fascination with this new motif, Picasso was, as was often the case with his works from the 1960s and 1970s, looking backwards and engaging in a conversation with the Old Masters. In exploring the motif of the reclining nude, he is said to have been particularly inspired by Goya’s striking La maja desnuda (The Naked Maja) (fig. 5). However, in contrast to both the classical paintings Picasso was deriving inspiration from at the time as well as the work of his contemporaries (in particular, Matisse, and his paintings of odalisques), Picasso’s depictions of the female nude are a distinctly powerful and intimate reflection on his relationship with the woman who was at the centre of his creative and domestic universe at the time.

As Marie-Laure Bernadac writes, in 1964, “after isolating the painter in a series of portraits, it was logical that Picasso should now paint the model alone: that is to say a nude woman lying on a divan, offered up to the painter's eyes and to the man's desire. It is characteristic of Picasso [...] that he takes as his model – or as his Muse – the woman he loves and who lives with him, not a professional model. So what his paintings show is never a ‘model’ of a woman, but woman as model. This has its consequences for his emotional as well as his artistic life: for the beloved woman stands for ‘painting,’ and the painted woman is the beloved: detachment is an impossibility” (Marie-Laure Bernadac, “Picasso 1953-1972, Painting as Model,” in ibid., p. 78).

Nu assis dans un fauteuil is a further variation on this theme, with the female figure now seated upright in an armchair – a compositional device which Picasso turned to again and again throughout his creative career. While varying in style and depicting different women that marked each period of the artist’s life, these figures, seated and fully attentive, generally served as a vehicle for expressing the palpable sexual tension between the painter and his model. From the soft, voluptuous curves of Marie-Thérèse Walter to the fragmented, near-abstract nudes of his surrealist work, and the exaggerated rendering of his later years, Picasso’s seated nudes have a monumental, sculptural presence, and are invariably depicted with a powerful sense of psychological drama stemming from the tension between the invisible artist and his sitter.

Picasso's Seated Women Through Time

What is, however, distinctive about Picasso’s depictions of Jacqueline as a female nude and what Nu assis dans un fauteuil serves as a particularly striking testament to, is the more affirmative and distinctly less tortured energy that they emanate. As Barbara Rose notes in relation to this,

“The affection Picasso felt for Jacqueline is unmistakable, both in photographs of the two as well as in his portrayals of her, where she is never disfigured or destroyed like his earlier lovers. […] He had depicted the other women in his life as violent beasts with sharp teeth or as hysterical harpies, but Picasso never portrayed Jacqueline as grasping or cruel, or as the enemy he feared could wound him. The obvious reason is that Jacqueline did not provoke Picasso. She soothed him.”

Brimming with life-affirming energy that distinguishes Picasso’s late work, Nu assis dans un fauteuil is one of the most powerful depictions of Picasso’s ultimate muse and lover, Jacqueline Roque, which the artist produced during the great late phase of his career. The present work makes an auction appearance for the first time, having historically featured in one of the last exhibitions held during the artist’s lifetime, Homage to Picasso for his 90th Birthday, organised jointly by the Marlborough and Saidenberg galleries in New York in 1971.