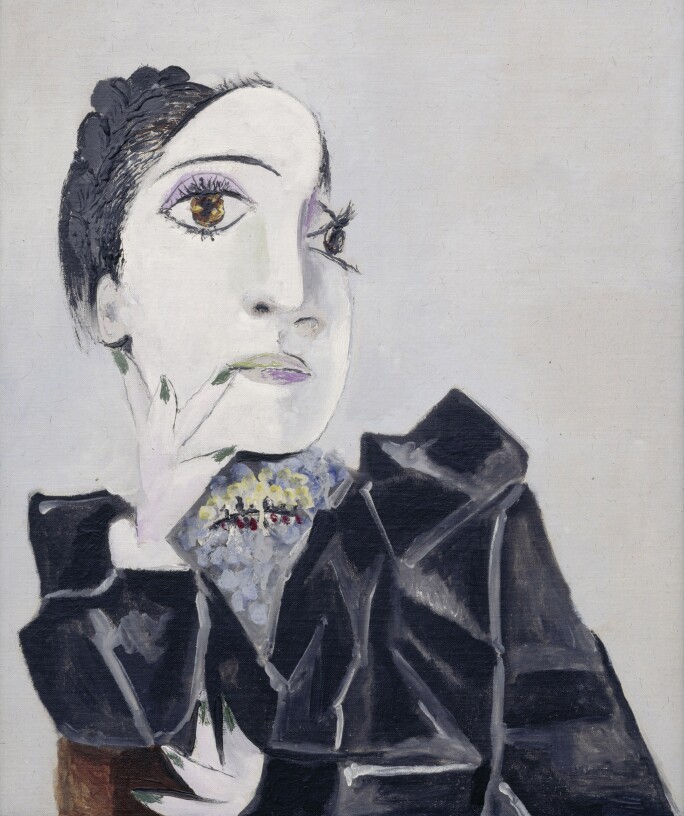

The 1930s were a key decade for Picasso. They began with his iconic portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walter and by 1937 he had also completed his great masterpiece Guernica. These works cast a light on the contrast between Picasso’s private world and his perspective on the wider world; on the one hand is a series of paintings filled with sensuality, celebrating love and desire, on the other, a monumental work en grisaille painted in response to an extraordinary atrocity. A polarization of extremes seems to characterise the decade for the artist, and this is nowhere more apparent than in his two lovers of the period: the blonde, youthful, guileless Marie-Thérèse Walter and the dark-haired, vulpine Dora Maar (figs. 1 & 2). Buste de femme accoudée, gris et blanc – a sublime portrait from 1938 – encapsulates the narrative of these differences and offers a powerful insight into the life and work of an artist at the height of his powers.

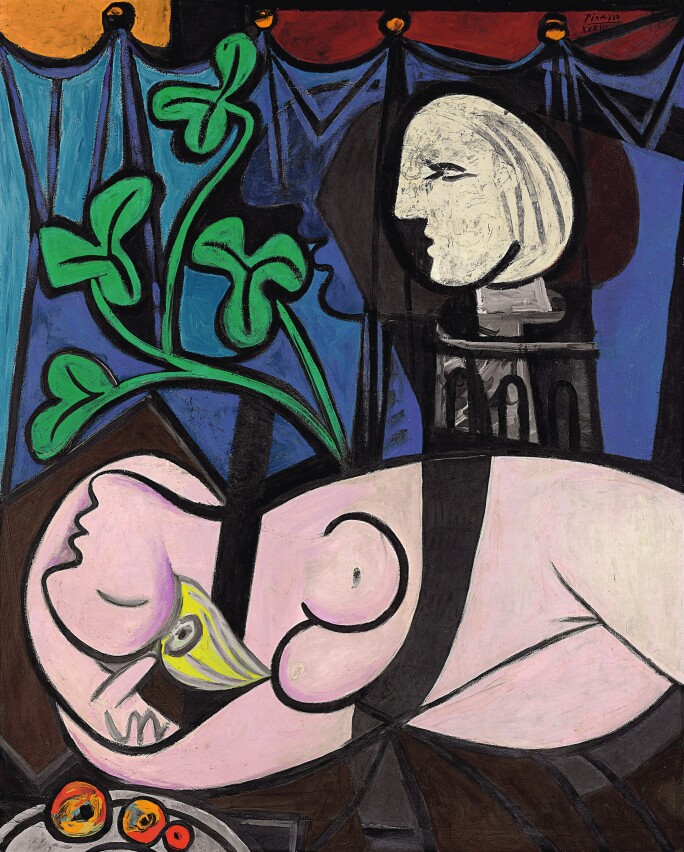

Picasso famously met Marie-Thérèse in 1927 as she was walking through Paris. As Walter recalled many years later: ‘I knew nothing - either of life or of Picasso [...]. I had gone to do some shopping at the Galeries Lafayette, and Picasso saw me leaving the Metro. He simply took me by the arm and said, “I am Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together”’ (quoted in Picasso and the Weeping Women (exhibition catalogue), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles & The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1994, p. 143). She would inspire some of his most powerful and sensual paintings (fig. 3): ‘Marie-Thérèse embodied for Picasso an ideal type – love, model and goddess. She offered him a release into sensuality and inspired the series of reclining, sleeping nudes of the early 1930s. Through Marie-Thérèse, Picasso discovered a new amplitude of form; less solemn than the monumental neo-classical nudes of the 1920s and with a promise of abundance and pleasure’ (Patrick McCaughey in Picasso (exhibition catalogue), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne & Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1984, p. 211).

By 1938, however, the nature of her relationship with Picasso had changed. Walter was the mother of his child (Maya, born in 1935), no longer quite the young ingenue he had swept off her feet a decade earlier, and perhaps more significantly, in 1936 a new woman had entered Picasso’s life. The artist met Dora Maar in early 1936 at the Café Deux Magots and was immediately enchanted by her intellect and beauty and by her commanding presence. Although still involved with Marie-Thérèse Walter and still married to Olga Khokhlova at the time, Picasso soon became intimately involved with Maar.

‘Colours, like features, follow the changes of emotions.’

Unlike the more gentle and easy-going Walter, Maar was an artist, spoke Picasso's native Spanish, and shared his intellectual and political concerns. Françoise Gilot commented on the women’s contrasting personalities noting that: ‘Marie-Thérèse had no problems. With her, Pablo could throw off his intellectual life and follow his instinct. With Dora, he lived a life of the mind’ (Françoise Gilot & Carlton Lake, Life with Picasso, New York, 1964, p. 236). This was probably the essential difference between the two women, and – like so much else in Picasso’s life – it was reflected almost immediately in his art. There is a notable shift from the sweeping curvilinear forms of Marie-Thérèse Walter that had dominated the artist’s œuvre since the late 1920s. Portraits of Maar tended to be more angular, to embrace a slightly more emphatic disarticulation of form, to represent her dynamic personality (fig. 6). Picasso often chose to depict both women in the same precise posture, sometimes even painting them both on the same day and the interplay between these works reflects the complex nature of Picasso’s feelings for the two women.

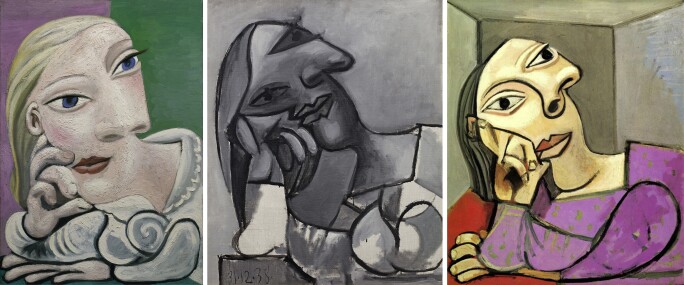

More intriguing still, are the works such as Buste de femme accoudée, gris et blanc that appear to accommodate both women at once. In the week after he painted the present work, Picasso produced two other femmes accoudées in colour (figs. 7 & 8) – the arrangement of their features is almost identical, but one has the brown hair denoting Maar and the other, the pastel palette and blonde hair that is associated with Walter. The grisaille colour tones of the present work make it impossible to identify one woman as the dominant presence in the painting; the smooth sweep of her hair and the languid sensuality in the eyes are typical of Walter, but there is something in the mouth that speaks purely of Maar.

© Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2022 / ‘Photo: akg-images

Picasso produced works in monochrome in every period of his career, fascinated by the different challenges and opportunities that a limited palette presented. In 1938 - the same year that the present work was painted - Gertrude Stein observed that ‘Picasso’s colour […], in itself, is a whole story’ (quoted in Picasso Black and White (exhibition catalogue), The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2012, p. 23). That is certainly true of the Buste de femme accoudée, gris et blanc where the absence of colour – and thus of certain identity – reveals the equal importance of both women at this moment in time. It also allowed Picasso a more expressive formal range. David Sylvester describes the reciprocal nature of Picasso’s work in black and white: ‘The need to isolate often governs Picasso’s use of colour. At different times he isolates blue, pink, black-and-white, and so on. This has both a positive and a negative aspect. The positive is the assertion of the chosen colour: it’s often said that Velazquez and Goya made a colour of black; Picasso’s black-and-white pictures isolate this strain in the Spanish tradition. The negative aspect is that absence of variety in the colour helps to isolate qualities of form’ (D. Sylvester in ibid., p. 23).

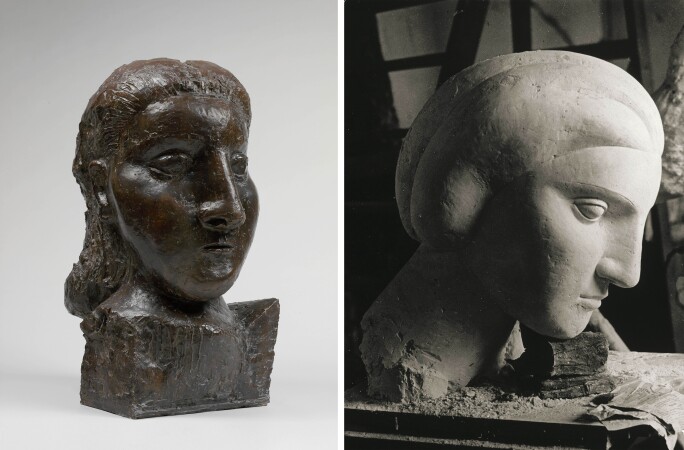

The qualities of form are particularly important in Picasso’s female portraits. One of the recurring tropes – that has its basis in Picasso’s cubist experiments of the 1910 – is a simultaneous presentation of both face and profile. In some paintings this is exaggerated, as in the 1931 Marie-Thérèse, face et profil (fig. 9) where the palette focuses attention of form, emphasising the duality of the artist’s presentation. In the present work, the colour similarly accentuates form but to very different effect. In Buste de femme accoudée, gris et blanc there is a glorious tonal range with the greys building and fading across the composition; this results in a chiaroscuro that is rarely seen in Picasso’s other work of this period. It imbues the work with a three-dimensionality that deliberately connects it to Picasso’s celebrated sculptures of Walter in the early 1930s and anticipates his sculptures of Maar in 1941 (figs. 10 & 11).

The fine handling of light and dark, and the overall framing of the composition suggests that Picasso may also have been thinking about photographic techniques when he painted this picture. Maar – already an established Surrealist photographer when she met Picasso – had introduced the artist to photography, teaching him how to use different cameras. When he started on his 1937 masterpiece Guernica she both worked as his assistant and produced a photo-documentary of the work in progress. A heightened awareness of photographic imagery may have influenced the composition of this monumental painting; the episodic passage of images across the composition has the cinematic quality of a newsreel or a photo-montage and is all the more powerful for the immediacy this conveys. Looking at Buste de femme accoudée, gris et blanc – painted only a year later in 1938 – it is hard not to think similarly of the black and white studio photographs of matinee idols that were commonplace at the time.

If the 1930s was a decade of contrasts, then Buste de femme accoudée, gris et blanc might very well be considered emblematic of the decade in the way that it acts as a fulcrum for the many opposing forces in the artist’s life, and particularly the two women who occupied the artist’s thoughts and imagination over the course of those years. In capturing them simultaneously in a single image, as Picasso does here, he adds a temporal quality to the picture – placing it in a precise moment when both women held equal sway. So like many of Picasso's best paintings, Buste de femme accoudée, gris et blanc acts as his diary, offering a unique and revelatory insight into the artist's life.