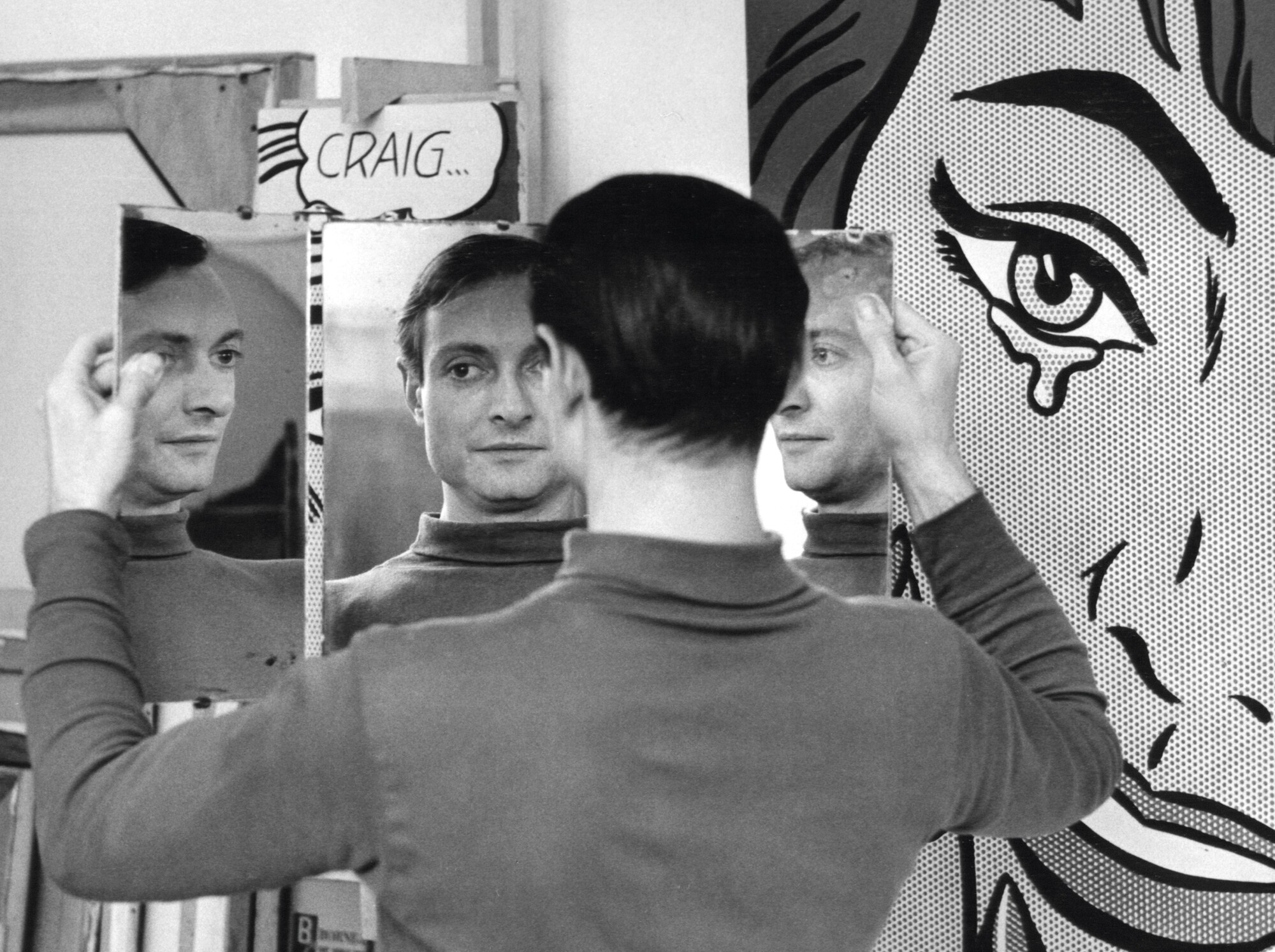

Mirror #9 elegantly captures Roy Lichtenstein’s singular ability to engage with canonical art historical themes through the motifs and idioms of twentieth-century consumer culture and, in doing so, interrogate conceptual and symbolic notions of art and illusion. Lichtenstein’s oeuvre is predicated on a semiotic investigation of the ways in which systems of representation allow us to conceptualize and interpret the world around us. Between 1969 and 1972, Lichtenstein produced a finite collection of Mirror paintings, through which he engaged with the representational strategies and tropes of mirrored surfaces in art history and contemporary advertising. Inspired by depictions of mirrors found in retail catalogues and magazines, Lichtenstein uses his unique artistic vocabulary to break down the codes inherent in reproduction and visual communication to their essential components. Mirror #9 thus stands as one of the most significant symbolic programs of Lichtenstein’s oeuvre, its subject persisting as a sign of artifice and illusion throughout the remainder of his prodigious career.

In the latter half of the 1960s, Lichtenstein devoted his practice to reinterpreting icons of art history through his signature Pop Art lexicon, rooted in the aesthetic strategies of twentieth-century mass production and consumer branding. After exploring canonical art historical periods, such as Classical Antiquity, Impressionism, and Cubism, Lichtenstein considered one of the most iconic and technically challenging motifs of Western painting since the Renaissance: the mirror. “In the Mirror paintings, Lichtenstein did not depart from his system of formal elements derived from his first comic-strip paintings but used it for very different ends. He continued to rely on the look of a painting as a reproduction of an original but refined the elements and altered the concept just enough to apply them to an exploration of abstraction. Now that he established his system of codes, he was free to improvise on any subject.” (Diane Waldman, “Mirrors, 1969-72, And Entablatures, 1971-76,” Roy Lichtenstein, New York, 1993, p. 189) Executed in 1970, Mirror #9 exemplifies this progression: ostensibly depicting a mirror with a curiously blank reflection, Lichtenstein graduates his signature Ben-Day dots across the canvas, at once entirely abstract yet cleverly evocative.

For each painting from the Mirror series, Lichtenstein uniquely interspersed his signature Ben Day dots, which refer to the mass-production technique used by newspaper printers, with areas of solid color in order to achieve the effect of a reflective surface. Here, the profusion of dots replaces the viewer’s reflection, suggesting a witty commentary on perception and the role of the artist. Like a Jasper Johns Flag, a Lichtenstein Mirror is as much a painted mirror as a painting of a mirror. Thus the Mirrors perfectly epitomize the conflict between reality and illusion that underpins Lichtenstein’s entire oeuvre. Mimicking consumer advertisements, Lichtenstein used simplified shapes to suggest the idea of a reflection, deconstructing not only the reality of his mirror subject, but also the artistic shorthand through which it is represented. As the artist himself explained, “Mirrors are flat objects that have surfaces you can’t easily see since they’re always reflecting what’s around them. There’s no simple way to draw a mirror, so cartoonists invented dashed or diagonal lines to signify ‘mirror’. Now, you see those lines and you know it means ‘mirror’ even though there are obviously no such lines in reality. If you put horizontal, instead of diagonal lines across the same object, it wouldn’t say ‘mirror’. It’s a convention that we unconsciously accept.” (The artist quoted in Michael Kimmelman, ‘Roy Lichtenstein at the Met, Portraits, Talking with Artists at the Met, the Modern, The Louvre and elsewhere’, The New York Times, 31 March 1995, p. C1)

Roy Lichtenstein’s Mirror Paintings from 1970 in Institutional Collections

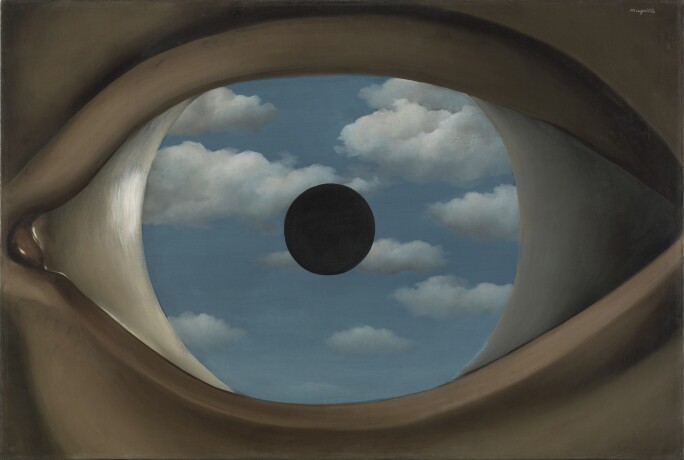

Although Lichtenstein’s compositions are most obviously rooted in twentieth century commercial aesthetic norms, the artist also engaged in a dialogue with canonical art historical conventions. Since the Renaissance, the mirror has appeared in the works of esteemed artists as a conceptual reference to the inherent illusion of the picture plane. In van Eyck’s celebrated Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, and Diego Velázquez’s renowned Las Meninas, 1656, the artists use the mirror to identify the perspective of the viewer and, in doing so, suggest the fundamental artificiality of the composition. Borrowing from the production methods of twentieth-century mass media, Lichtenstein’s practice explores representation and illusion in the modern day. His Comic Strips, Girls, Interiors, and Mirrors series engage the viewer in the ways in which contemporary commercial culture creates a false sense of reality for the consumer. Transfixingly beautiful and precisely rendered, Mirror #9 perfectly embodies the underlying concerns of Lichtenstein’s career: to examine the signs and symbols that give meaning to contemporary life.