Expert Voices: Tom Eddison on Francis Bacon's Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes

“Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes marked Bacon's consummation of the small triptych format... The restricted palette of mainly crimson and white on a textural black ground is masterly, as are the energy and motion of the brushstrokes and smearing of the wet pigment. Indeed, Bacon’s execution has a power, skill and confidence that he scarcely ever surpassed in this format.”

Photo by Derek Bayes

Artwork: © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022

Painted in 1963, Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes is unequivocally one of the finest and most accomplished small portrait triptychs ever created by Francis Bacon. The first named portrait of Henrietta Moraes in Bacon’s oeuvre, and the second ever triptych executed in the iconic 14 by 12 inch canvas format, this is a work of great historical importance and unrivalled execution. Delivering a seamless interlocking of paint and image, these three canvases epitomise the consummate painterly virtuosity and uncompromising power of their creator. In his Catalogue Raisonné entry for this painting, Bacon scholar Martin Harrison praises this very work, identifying it as the artist’s “consummation” of the small portrait triptych, in which “Bacon’s execution has a power, skill and confidence that he scarcely ever surpassed in this format” (Martin Harrison, Ed., Francis Bacon Catalogue Raisonné, Volume III 1958-71, London 2016, p. 733). In a manner unparalleled by any before or since, Bacon had an ability to capture beauty, pathos and violence in a flick of paint, a talent that surpassed a translation of mere form and likeness to deliver something closer to the raw fact of existence. The present work delivers this with aplomb: here we bear witness to a portrait of a legendary Soho Bohemian, a subject whose unconventional, uninhibited lifestyle and gregarious nature is writ large across each canvas. Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes was the last picture included in Bacon’s early Catalogue Raisonné, to which its editor Ronald Alley wrote that it was “painted partly from life”; a positing that situates it as one of the final works Bacon executed in this manner, as from 1962 Bacon began principally to rely on photographs of his friends/subjects taken by John Deakin (Ronald Alley and John Rothenstein, Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné and Documentation, London and New York, 1964, p. 155) Reinforced by Bacon’s own proclivity for the peril of life’s roulette wheel, Moraes’s very essence projects forth through a confluence of daring brushwork and imagination: a powerful coalescence of colour, texture and form that radiates sheer vitality. Hung upon an armature of disfigured facial features contained by the focussed proportions of these three canvases, the present triptych harnesses chaos, chance, beauty, and violence to deliver images of astonishing intensity and carnal grace.

Created during an extraordinary decade buttressed by two major retrospectives – the first at London’s Tate Gallery in 1962 and the other at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1971 (the present work was prestigiously included in the latter) – Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes was acquired by William S. Paley from Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, New York, almost immediately following its execution in 1963. Indeed, only months prior, Paley had also acquired Bacon’s first triptych in this format, Study for Three Heads of 1962 – a painting in which Bacon’s recently departed lover, Peter Lacy, flanks a contorted self-portrait of fraught emotion. Considered one of the most forward-thinking, generous, and influential collectors of the Twentieth Century, William S. Paley played a key role in the development of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Beginning in 1937, Paley was instrumental in defining an institution only established 8 years previously and over the next five decades he would take on major roles within the organisation including trustee, president, and chairman. Today, many of the museum’s most treasured works are those donated from Paley’s collection, including Picasso's Boy Leading a Horse (1905-06) and The Architect’s Table (1912), Cézanne’s L’Estaque (1882-83), and Redon’s Vase of Flowers (circa 1912-14). Following his death in 1990, Paley’s two important Bacon triptychs would go to MoMA on long-term loan, with Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes coming to Sotheby’s directly from the museum where it has resided for over thirty years.

Image: © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved. DACS/Artimage 2022

Photo: John Deakin

Private Collection

Image/Artwork: © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved. DACS/Artimage 2022

As a debut work in Bacon’s newly forged small-triptych format, Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes announced a sea-change in Bacon’s practice. The motifs and tropes of the previous decade were abandoned in favour of unadorned and focussed portrayals of the human form in closely cropped and consistent proportions. Alongside the small 14 by 12inch canvas format, Bacon would also standardise his larger production in panels measuring 78 by 58 inches: from 1962 onwards these two formats provided the structural basis for the rest of Bacon’s career. Where the large panels acted as arenas for Bacon’s operatic musings on the human condition, the smaller canvases were to become, in the words of esteemed art historian John Russell, “the scene of some of the artist’s most ferocious investigations” (John Russell, Francis Bacon, London, 2001, p. 99). With Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes Bacon powerfully laid down the harrowing introspective quality and unadorned immediacy that would become intrinsic to the small portrait triptychs.

Image: © The Museum of Modern Art/Scala, Florence

Artwork: © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved. DACS/Artimage 2022.

Private Collection

Image: © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

Artwork: © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2022

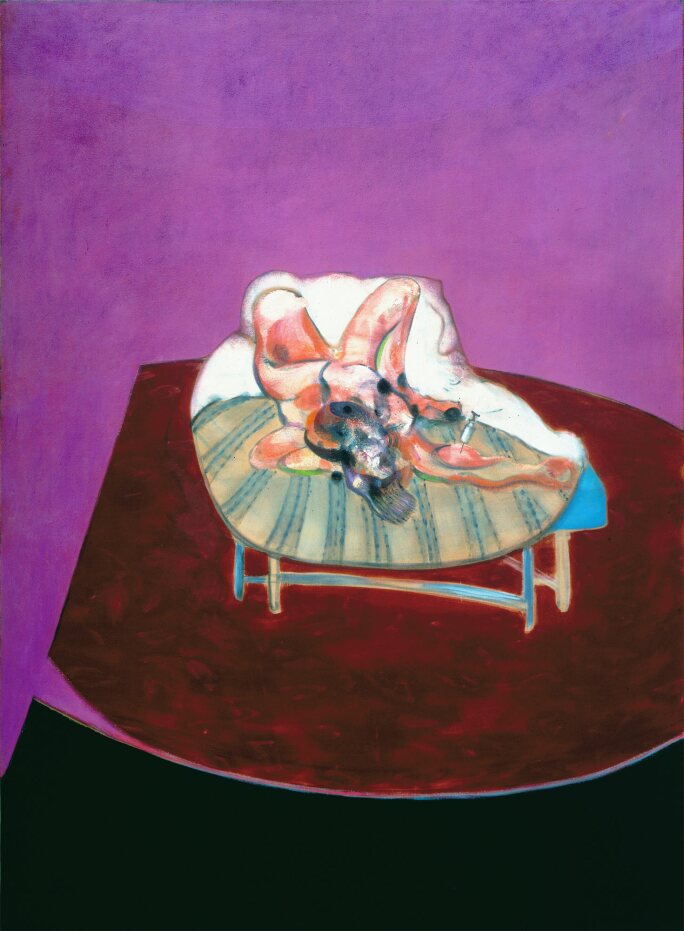

The second small scale triptych ever created by Francis Bacon and arguably his finest, Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes is a tour-de-force of visceral technique and painterly invention. Tightly focussed and with nowhere to hide, three head-and-shoulders images of Moraes play out as a sequence of superimposed states. Here we see Bacon truly define the power and impact possible within the confines of three 14 by 12 inch canvases. Across a bituminous, tar-like ground of thick texture, Moraes’s likeness emerges in swipes of crimson and white. The more refined silhouette of the left-hand canvas – a form that exudes the influence of Picasso’s Dora Maar – gives way to two gnarled and contorted images accented with tones of green, blue, and purple. In his Catalogue Raisonné entry Martin Harrison further expounds upon the virtuosity of this very work: “The restricted palette of mainly crimson and white on a textured black ground is masterly, as are the energy and motion of the brushstrokes and smearing of the wet pigment.” (Martin Harrison, Ed., Francis Bacon Catalogue Raisonné, Volume III 1958-71, London 2016, p. 733). Even when making the comparison to Bacon’s other great small triptychs of this period – notably Three Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer (1963) and Three Studies for Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964) which share the same bituminous ground and dominant red/black colour palette respectively – it is clear that Bacon’s Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes embodies his greatest achievement in this format. The artist clearly thought as much; in John Russell’s monograph he recalls Bacon comparing this triptych to Giorgione’s self-portrait in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Brunswick, stating that both seem to say “the most that can be said in paint at this time about human beauty” (Francis Bacon quoted in: Ibid., p. 100).

This triptych announces Moraes’s first named presence in Bacon’s oeuvre; however, as noted by Martin Harrison, her bodily form had already found expression as early as 1961 in works such as Crouching Nude (1961). By 1963, Moraes had become the locus of some of Bacon’s most powerful full figure paintings and expressions of the nude such as the extraordinary Lying Figure with Hypodermic Syringe (1963). Though her face is entirely obliterated in this work, this prophetic image (it eerily prophesised Moraes’s later intravenous methamphetamine addiction) is the first in a series of large-scale reclining nudes that Bacon would paint based on nude photographs taken by John Deakin. Across Bacon’s oeuvre, the number of paintings after Moraes clearly demonstrate the great depth of invention sparked by her likeness and personality. Indeed, where male subjects – friends, lovers and fellow artists – feature heavily in Bacon’s work, Moraes recurs with a frequency that reflects his fascination with her. In sum there are 4 named small head triptychs of Moraes, 2 single small portraits, 5 large format portraits, and 9 unnamed figure paintings, all of which pulsate with animal vitality and unchecked verve.

Francis Bacon’s Large-Scale Portraits of Henrietta Moraes

In comparison to depictions of Bacon’s other great female muse, Isabel Rawsthorne, whose portrayals are generally less distorted, Moraes’s visage and bodily countenance deliver an unadorned corporeal vitality and charged bestial energy; closer perhaps to the ‘brutality of fact’ which drove Bacon’s artistic impetus. Where Rawsthorne – friend of the Parisian cultural elite – represents nobility and an almost masculine heroic spirit in Bacon’s work, Moraes embodies fleshiness, femininity, unvarnished vivacity and instinctual carnality. As in the present triptych, and as played out across the many outstanding large figure studies depicting her form, the extreme facial and corporal distortions of Moraes’s likeness cast her as a remarkable vehicle for Bacon. In a photograph of the artist taken by Derek Bayes in October 1963, the centre and right-hand canvas of the present work appear on Bacon’s easel positioned at the artist’s head height. With one hand raised in an expression of intensity and focus, Bacon seems to complete the triptych. In this photograph as in the fully finished Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes, painter and subject form an indelible confluence. Moraes was the ultimate female subject for Bacon. A notorious bonne vivante, sexually uninhibited, unconventional and a serious drinker, she captivated Bacon both physically and spiritually; in many ways she held a mirror up to his own untamed character which yearned for the unvarnished underbelly of life.

Image: © The Estate of Francis Bacon. DACS/Artimage 2022.

Private Collection

Image/Artwork: © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images

Born Audrey Wendy Abbott in India in 1931, Henrietta Moraes had a challenging and unconventional childhood. Her family returned to England when she was still very young, and after many years living with her fearsome, often violent grandmother and having attended various schools in different parts of the country, Moraes came to London at age eighteen to begin Secretarial College. With a spirited character, restless nature and little talent for shorthand, she abandoned her education and started work as a life model in art schools across London. Three marriages later and Audrey Abbott had become Henrietta Moraes: her final and most well-known moniker given to her by husband number three, the poet Dom Moraes. It was through her first husband however, the documentary filmmaker Michael Law, that she would become a stalwart feature of the Soho set, among whose notorious troop was of course Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. In her autobiography published in 1994 – a book that is both a wonderful memoire of 1950s/60s Soho Bohemia and a vivid account of a life less ordinary – Moraes records her first impressions of both artists:

“Two other people that I was determined to make friends with because I felt so drawn to them were Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. They were both young, not particularly well-known painters, but Lucian’s hypnotic eyes and Francis’s ebullience and charming habit of buying bottles of champagne proved irresistible…”

Francis Bacon’s Small Portrait Triptychs of Henrietta Moraes

Though married at the time, Moraes would have an affair with Freud during this period and was painted for the wonderfully tender portrait Girl in a Blanket of 1952 in which Moraes sits partially covered on the edge of Freud’s unmade bed in his Paddington studio. This work presages Bacon’s own portrayals by almost a decade. Of Bacon, Moraes fondly recalls:

“When I was eighteen, I had spent almost all my mornings, afternoons and evenings with him, dined along with him at Wheeler’s, oysters and Chablis, gone with him to the Gargoyle, listened to the wit and wisdom which flowed almost continuously from his lips. Sometimes I was aghast at the scathing sarcasm which bubbled out of him, but it was never directed at me. At every meeting I had learned something new from him, been captivated, spellbound. Wherever he appeared, the air brightened, groups of people were animated, electricity hummed and buzzed and bottles of champagne arrived. I had learned so much of the ways of the world from him and, though at the time I had not properly understood half of his teaching, it had nevertheless, willy-nilly been assimilated.” (Ibid., pp. 72-73).

Indeed, by the time Bacon came to paint Moraes, ten years had passed; aged 30 or 31 at the time, Moraes recalls Bacon’s suggestion that she pose for him:

“One night I was having a drink in the French Pub with Francis Bacon and Deakin and others. Francis said, ‘I’m thinking of painting some of my friends and I’d like to do you but I can really only work from photographs, so, if it’s OK, Deakin will come round to your house and take them. I’ll tell him what I want. You are beautiful, darling, and you always will be, you mustn’t worry about that.’” (Ibid., 71).

This would have been around 1962 and was the point at which Bacon began commissioning his drinking partner, friend, and Vogue photographer, John Deakin to capture Moraes and the protagonists of his Soho enclave. The resulting photographs formed a repository of visual aids for Bacon, whose lasting impact is plainly manifest across the host of astonishing paintings that followed; indeed, at the time of his death in 1992 over three hundred of these images were found scattered and strewn across Bacon’s studio. Among these, nude and clothed, full figure and head shot, interior and exterior, paint stained, crumpled and folded, Deakin’s photographs of Moraes feature heavily.

Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA

Artwork: © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS/Artimage 2022.

Moraes’s appearance in Bacon’s oeuvre thus illustrates a seismic shift at the beginning of the 1960s. Moving away from emblematic forms – such as those extrapolated from Velazquez’s Pope, Muybridge’s The Human Figure in Motion, motifs from Van Gogh and Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin – Bacon looked to capture the ‘fact’ of human behaviour in a more direct non-illustrational way. Realising the need for a physical armature upon which to hang this ‘energy’ and ‘living quality’, Bacon turned to his inner social circle, and specifically those with whom he shared a similar instinctual and risk-taking attitude towards life. Bacon’s principal subject thus became the people he knew best: combining memory with Deakin’s aide-memoires, alongside Moraes Bacon painted George Dyer, Isabel Rawsthorne, Lucian Freud, and Muriel Belcher, and in so doing, created some of the most astounding and inventive portrait studies of the Twentieth Century. Delivering an extraordinary coming together of familiarity and total originality, the small portrait studies signify the ultimate record of sensation in Bacon’s work. To quote art historian William Feaver: “‘Studies’ or exercises though they are, these small paintings are central to Bacon’s art. The scale of a bathroom mirror-image makes them one-to-one, and when they are paired, or grouped in threes, the differences animate them. No rooms, no thrones, no perfunctory landscape settings are needed. Without context or posture, the heads have nothing to do but look, sometimes at one another, and wait” (William Feaver, ‘That’s It’ in: Exh. Cat., London, Marlborough Fine Art Ltd., Francis Bacon 1909 - 1992 Small Portrait Studies, 1993, p. 6).

EARLY SMALL SCALE TRIPTYCHS

Bacon’s portraits are an enactment of his own thoughts on the nature of real friendship; the artist is famously quoted saying: "I’ve always thought of friendship as where two people really tear each other apart", indeed, in his portraits Bacon mercilessly pulls, rips and cleaves the intricacies of his friends’ likenesses until their flayed countenances distil some essential physical and pictorial truth (Francis Bacon quoted in: Michael Peppiatt, Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, London, 2009, p. 257). Exploiting familiarity to his advantage, Bacon freely manipulated and wrestled with the physiognomy of those closest to him to engender an elemental painterly distillation in which facture and expression are resolutely interlocked. Representation is deconstructed to the point where features become indiscernible and physical states are superimposed. Nevertheless, the end result is unmistakable in subject. As outlined by John Russell: “although the features as we know them in everyday life may disappear from time to time in a chromatic swirl of paint or be blotted from view by an imperious wipe with a towel, individual aspects of the sitter are shown to us, by way of compensation, with an intensity not often encountered in life” (John Russell, Francis Bacon, London, 2001, p. 124).

Emulating mug-shot proportions of a photobooth image or ‘police record’, the unadorned immediacy of Bacon’s small portraits radiate endurance, nervousness, and involuntary mannerisms: these heads truly embody Bacon’s desire to paint as close to the ‘nervous system’ as possible. Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes consummately epitomises the breathtaking power of these small triptychs, and indeed, Bacon’s unique ability to harness the essence of being – its chaos, the ludicrous chance of life itself, it’s terrible beauty – is nowhere more apposite. Beyond mere form and likeness, these are remarkable portraits as unrestrained and exuberant as Moraes’s uninhibited and extraordinary life.