Owing to their inherent fragility, fifteenth-century portraits painted in oils on paper and laid down on panel are today of the greatest rarity. This striking small portrait, with a its reflective, even romantic young sitter, provides an exceptionally fine example. Painted around the final decade of the fifteenth century, this painting poses intriguing questions, not only in terms of its origin, but also as to its original context and function, which remain unclear. It was most probably painted within the territories of the Habsburg Burgundian Netherlands, which then included the Low Countries and parts of northern France, a region which had exerted a huge influence upon courtly art and culture across Europe in the fifteenth century. It has been suggested that it is the work of the anonymous late 15th-century painter known as ‘The Master of the Princely Portraits’, who was active in Brussels where he painted a series of half-length portraits of members of the Ducal Court. The sitter himself has not been identified but his black tunic is in keeping with Burgundian court fashion of the same period. The red background against which he is set was favoured by painters of the Brussels school, but was equally to be found in French and German works of this date, and the possibility that the painter was French or was trained or active in Paris as well as the Netherlands has also been put forward. The portrait here was probably painted first on paper and then glued to its panel, and the skilful use of this rare medium raises the further intriguing possibility that the artist may have worked as a manuscript illuminator as well as a panel painter.

RIGHT: Fig. 2 Detail showing initial

Identity and Function

The identity of this pensive young man remains frustratingly elusive. Despite the presence of a coat of arms on the original frame (fig. 1), this too remains unidentified, and although it confirms his high social status, as yet no documents or comparable works have come to light that that could otherwise confirm his identity. The sitter is shown wearing a simple unadorned black tunic fastened at the neck. He wears an equally plain but large round black wool hat, upon which is pinned a circular pewter pilgrim’s badge, perhaps indicating a recent or intended pilgrimage, or simply intended as a reflection of his piety.2 His under cap is fastened with a ribbon pinned by a gilt gothic letter ‘A’, possibly an indicator of the sitter’s initial or that of his family (fig. 2). An identical brooch in the form of the letter ‘A’ with an attached pearl, belonged, for example, to Adolph of Cleves, Lord of Ravenstein (1425–1492), the nephew of Philip the Good of Burgundy.3 It is worn by him in a near-contemporary portrait formerly in the Château de Rumillies and today preserved in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tournai and it appears again in the foreground of a panel depicting the Wedding at Cana, which forms the left-hand wing of the Triptych with the Miracles of Christ preserved in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (figs 3 and 4) which he probably commissioned and which was painted by the Master of the Princely Portraits and other Brussels painters around 1490–95.4 Its significance in the present portrait, however, remains unknown.5 A similar letter ‘B’ adorns the hennin worn in a Portrait of Margaret of York, later Duchess of Burgundy (1446–1503) in the Louvre, which has also been attributed to the Master of the Princely Portraits, although in that instance seemingly only as a purely decorative motif.

RIGHT: Fig. 4 Detail of The Wedding Feast at Cana (fig. 3), showing figure wearing brooch in the form of the letter ‘A’

In addition to these emblems, our sitter holds prominently in his right hand a ring, set with a dark blue stone (sapphire?). The significance of the ring in this portrait is not known, but similar small-scale portraits incorporating this motif were already familiar in Netherlandish art by this date, and had, for example, previously been used by Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) earlier in the century. In the case of his portrait of the Bruges goldsmith Jan de Leeuw of 1436, today in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna,6 for instance, the sitter holds a ring representative of his profession as a goldsmith. The motif is found again in the earlier and smaller portrait of the unidentified Man wearing a blue chaperon painted around 1430 (fig. 5) and today in the Muzeul Naţional Brukenthal in Sibiu, Romania, but here it is more generally thought to be an indication of a betrothal portrait.7 It is quite possible that the present panel was conceived as an individual portrait study or pattern for a portrait such as these. There are no signs on the frame that it was ever intended to form one side of a pair of portraits—for which the male sitter would by tradition have been painted facing in the opposite direction—but the idea remains that it may have been intended for a betrothal portrait, for which the sitter’s conspicuous emblems of love and piety would have been well suited.

Support, Dating and Function

In her very detailed analysis of the present work published in 2015 Catheline Périer-D’Ieteren rightly described it as constituting ‘one of the rare known examples of a Flemish late fifteenth-century portrait painted in oil on paper laid down on an oak panel’. Currently, only around half a dozen examples of Netherlandish or early French works of this type dating from 1500 or before are known.8 The paper here has been laid down on a simple integral frame made from a single piece of eastern Baltic oak, the wood typically used for Netherlandish paintings of this period. Recent dendrochronological analysis by Ian Tyers has suggested a likely terminus post quem of c. 1489 for the panel, with a likely date of usage before c. 1523, thus entirely consistent with the style of the portrait itself and its likely place of creation.9 This would seem to confirm that the paper was laid down early on, perhaps soon after completion of the painting, or else as the result of a tear to the bottom edge. The paint was applied directly to both the paper and the panel without any prior grounding. A small uncovered band of circa 7 mm. along the bottom edge suggests that the panel was slightly too large for the sheet; this edge was repainted after completion, an indication that the portrait was probably painted upon the paper before being glued to its support. The frame was originally painted green, but has since been re-gilded at an unknown date and only the coat of arms remains.

The precise purpose of works such as this painted in oils on paper (or parchment) is not yet fully understood, but certainly had antecedents. Flemish painters in the 15th century were said to have used a long-established late medieval tradition of workshop models painted on paper or parchment that were glued to panel supports for use in the studio, or which were attached to larger (presumably religious) panels in the course of their execution.10 As Maryan Ainsworth has observed, the greater transparency of paper – probably achieved by coating in linseed oil prior to painting – may have provided a simple and useful means of tracing a design or master drawing in the artist’s workshop which could then be worked up in paint.11 These could then have been used as individual studies preparatory for a large composition, such as the Study of the head of an old man from the circle of Hugo van der Goes in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which dates to around 1470–75.12 Others might simply have facilitated the efficient production of versions of court portraits or popular religious compositions in the workshop, which were in great demand for private devotion in cities such as Brussels as the fifteenth century was drawing to a close. If the present painting was originally conceived as a preliminary study for a larger portrait, none has survived.

Style and Attribution

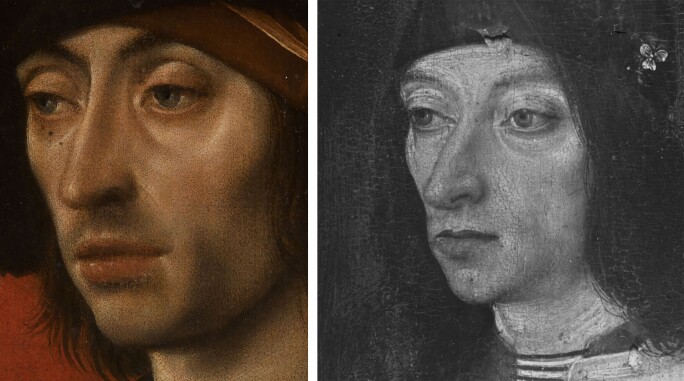

In 2015 Catheline Périer-D’Ieteren was the first scholar to propose an attribution for this panel to the ‘Master of the Princely Portraits’, a painter working in Brussels in the last quarter of the fifteenth century responsible for a stylistically coherent group of portraits of noble sitters almost exclusively drawn from the ranks of the Ducal Court of Burgundy. The actual identity of this artist has long remained elusive.13 His pseudonym was first given to him by Max Friedländer, who started to construct his œuvre around four of these portraits, namely those of Engelbert II of Nassau, 1487 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), A man of the Fonseca family, 1480s (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam), Louis of Gruuthuse, c. 1475–80 (Groeningemuseum, Bruges) and the Portrait of Jan Bossaert, formerly in the National Museum in Poznań, and now in a private collection (fig. 6).14 All are typically of half-length format, and all painted directly onto panel, nearly all with the painted red backgrounds favoured by the Brussels school. Some bear the coat of arms of their sitters on the reverse, others on their frames, which are themselves decorated with elegant polychromy.15 The physiognomies of the sitters are distinguished throughout by their long thin noses, large and heavy-lidded eyes and full lips, and slender physiques. Of the group, the likeness of Jean Bossaert unquestionably comes closest to the present portrait in terms of features and mood (figs 7a–b); the treatment of the facial features, notably the eyes, is very comparable to that of the Young man holding a ring but lacks the latter’s sense of volume and fuller modelling in terms of light and shade.

RIGHT: Fig. 7b Portrait of Jean Bossaert (detail)

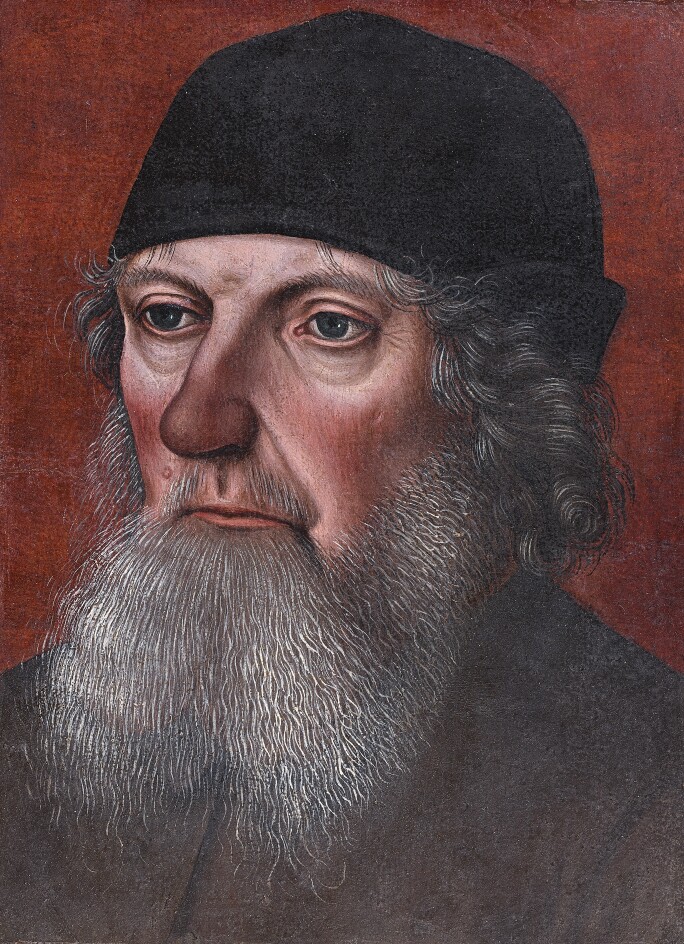

None are painted in oils on paper, and thus far only one other such work has been associated with the Master of the Princely Portraits. This is a small Head of a bearded man,16 (fig. 8) which appears to be a study or workshop model related to a panel depicting a Portrait of a man as Saint Andrew in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid,17 both of which have been attributed to the Master by Catheline Périer-D’Ieteren.18 This too is painted in oil on paper, but laid down onto canvas rather than panel, probably at a later date. Its original purpose may therefore have been similar to the study from the circle of Van der Goes now in New York. In its facture and detailed appearance, however, this study seems quite different in style to the present work. Indeed, for all their many similarities, the Young man holding a ring seems to remain apart from the Princely Portraits group, not only by reason of its style, but also by virtue of its bust-length format, through which the sitter fills almost all of the picture plane, and, of course, the fact that it is the only one that was painted directly onto paper and then laid onto panel. It is, in addition, lacking the distinctive frame that is typical of that group. There are, however, sufficient and undeniable parallels between it and the works of the Master of the Princely Portraits to suggest that it too may have been painted in Brussels, or painted by an artist trained there in the milieu of the Ducal court.

As Périer-D’Ieteren has observed, this facility to work in different media might indicate that the artist worked as an illuminator as well as a painter of panels. She cites the example of the famous Ghent-born illuminator Lieven van Lathem (c. 1430–1493), who worked at the Burgundian court, not only for Charles the Bold and Louis de Gruuthuse, but also later for Maximilian I and Mary of Burgundy. Lieven is also said to have painted works on panel, but no examples survive. His brother Jacques (fl. 1493–1522) was court painter to Philip the Fair, and interestingly his son Lieven van Lathem the Younger also worked as a goldsmith in the service of Philip the Good. More recently Stéphanie Deprouw-Augustin has proposed that the illuminator and painter Jean Beugier (fl. 1468–1505), who was active in Amiens, Brussels and Bruges, may be identifiable with the Master of the Princely Portraits, and that the initial ‘B’ on the Portrait of Margaret of York in the Louvre may be his monogram.19 Beugier’s principal work, the Tree bearing the fruit of Eternal Life now in the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, was commissioned by Antoine de Coquerel for the Confrérie du Puy Notre-Dame d’Amiens in 1499 and completed in 1500. Although only broadly similar in style, it would not be altogether fanciful to see the present work in the light of a study on paper for one of the many portrait heads incorporated in a larger work of this kind.

RIGHT: Fig. 10 Jean Perréal, Portrait of Pierre Marin de la Chesnaye(?), 1493. Oil on walnut panel, 29 x 24 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © Wikimedia

This process of working in oils on paper was not, of course, confined purely to the Netherlands, for parallel developments occur at the same date in other countries and regions still greatly influenced by Burgundian traditions and practices. By far the most important of these was France. Here, for example, Jean Perréal (c. 1455–c. 1530), known as Jean de Paris, worked as painter, architect and illuminator to three kings of France—Charles VIII (1470–1498), Louis XII (1462–1515) and Francois I (1494–1547). Although Perréal’s career as a painter and fame as a portraitist is well documented, certain examples of his work are harder to come by. We know that he worked on paper, and in terms of small-scale portraits, his finest example of his work in this medium is undoubtedly his miniature portrait of his friend the Lyonnais poet Pierre Sala, equerry to Charles VIII, bound within a volume of his love poems, the Énigmes, and today in the British Library (fig. 9). In oils his two most comparable works are the paired portraits of Pierre Marin de la Chesnaye(?) and Jean de Besse(?) in the Louvre, both painted on distinctively French walnut panels (fig. 10). We know too that the anonymous Master of St Giles was a Franco-Flemish painter who was probably French in origin but whose awareness of and debt to Netherlandish models suggest that he was trained in the Low Countries before settling in Paris around 1500. His Virgin and Child with a dragonfly in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, for example, is also painted in oil on paper laid on panel, so the method was clearly familiar to him, but his work as a portraitist, such as the small Portraits of a gentleman and his wife in the Musée Condé at Chantilly, displays a drier and more crisply realistic style.

These simultaneous similarities and discrepancies in style highlight the difficulty in establishing a secure date or locale for this memorable little painting. Indeed, they suggest that it is probably too narrow to think of the author of the Young man holding a ring purely in terms of a single location, and better perhaps to imagine him in the context of the wider Burgundian artistic heritage in the later fifteenth century. Similarities in costume and emblems reflect the date and social status of his patron, and possibly his locale, but they provide no firm clues as to the portrait’s authorship. Even the precise purpose of his relatively rare choice of medium is not known for certain. Although he is perhaps most likely to have been active in Brussels the artist responsible for the Young man holding a ring may have been born or trained elsewhere in the Burgundian Netherlands, which included Flanders as well as the northern provinces bordering Germany, or perhaps in France, later moving to work in Paris or Brussels. Whatever his origins or place of activity, he leaves a remarkable and possibly unique legacy.

Note on Provenance

This portrait has the distinction of having remained in the same family collection for over two centuries. It is possible that it may have formed part of the Clerk family collections from as early as the 17th century. John Clerk (1611–1674) enjoyed a profitable career as a merchant in Paris between 1636 and 1646, acting as a factor for shipping goods from Europe to Scotland, including many paintings, among them works attributed to Rembrandt and Brueghel. His own collection, no doubt a by-product of his entrepreneurial activities, was housed at Penicuik, the estate and barony of which he had purchased in 1646. Although the extensive family archives provide a detailed account of many of these transactions, it has not yet been possible to identify the present painting among them. The picture could have been acquired by several of his descendants, who proved to be inveterate travellers and collectors in their own right. His son Sir John Clerk (1649–1722), created a baronet in 1679, also studied in Paris, and travelled throughout the Netherlands and France. His son Sir John, the 2nd Baronet (1676–1755) was educated in Leiden, and travelled extensively in Holland and Germany, making an early Grand Tour to Italy in 1697–99, and was a collector and antiquarian of some repute. His son James (1709–1782) succeeded his father as 3rd Baronet in 1755, by which time he too had made his tour of Italy, including Florence, Pisa and Rome between 1732–34, and become an important patron of Imperiali and Runciman. It was Sir John, 2nd Baronet, who was the builder of the great Palladian mansion at Mavisbank between 1723 and 1727, where the present painting is thought to have hung. Mavisbank left the family following the death of Sir Robert Clerk (1722–1814), the fifth son of Sir George Clerk, 4th Bt, and this portrait was probably inherited with his collections by his nephew James Cheape (1746–1824), who bought Strathtyrum in 1782, where this picture is first recorded for certain.

1 The inscription may be roughly interpreted to mean that Massys was converted to a painter by conjugal love. Lorne Campbell has kindly pointed out that such a story was included in the Latin verses by Dominicus Lampsonius which accompanied Johannes Wierix’s posthumous engraving of the painter, made in 1572.

2 The image on the badge is indistinct but may depict a ship. A similar motif appears, for example, on the popular Pilgrim Badge of Henry VI of England, which was associated with the religious cult that arose after his death in 1471.

3 The pearl is suspended from the junction of two central stems, which Périer-D’Ieteren interprets as forming the sitter’s initials ‘AC’. A derivative likeness dated to 1489, is preserved in the Museum Kurhaus in Kleve.

4 For an analysis of the wing see C. Périer-D’Ieteren, ‘Apport à l’étude du ‘Retable de la Multiplication des Pains’ de Melbourne: I. Le volet des ‘Noces de Cana’, in Annales d’Histoire de l’Art et d’Archéolgie, XIV (1992), pp. 7–25.

5 The use of the character was not confined to this medium and was conceivably widespread. The same symbol or monogram was employed, for example, by the anonymous French illustrator of the famous incunabula La mer des hystoires published by Jehan du Pré in Lyon in 1491; G.K. Nagler, Die Monogrammisten, I, Munich 1920, p. 7, no. 16.

6 Inv. no. 946; oil on panel, 24.5 x 19 cm.

7 Inv. no. 354; oil on panel, 19.1 x 13.2 cm.; The Age of Van Eyck; the Mediterranean World and Early Netherlandish Painting 1430–1530, exh. cat., Bruges 2002, p. 233, no. 18.

8 In addition to the present work these include, for example: Circle of Jan van Eyck, Saint Jerome, c. 1435 (Detroit Art Institute); Circle of Jan van Eyck, St Francis of Assisi receiving the stigmata, c. 1430–32 (Philadelphia Museum of Art); Circle of Hugo van der Goes, Study of an old man, c. 1470–75 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); Attributed to the Master of the Princely Portraits, Study of a bearded man, 1490s (Bob Haboldt & Co., New York); Jean Perréal (?), Portrait of a Man, 1490s(?) (P. & N. de Boer, Amsterdam); and the Master of St Giles, Virgin and Child with a dragonfly, c. 1500 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Examples of parchment laid to panel include the anonymous Portrait of Lysbeth van Duvenvoorde, c. 1430 (Mauritshuis, The Hague); Petrus Christus, Head of Christ (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); and Geertgen tot Sint Jans, The Virgin and Child (Ambrosiana, Milan).

9 Dendrochronological Consultancy Report 1633, May 2025.

10 H. Verougstraete, A. De Schryver and R.H. Marijnissen, ‘Peintures sur papier et parchemin marouflés au XVe et XVIe siècles. L’example d’une Vierge et Enfant de la suite de Gerard David’, in Le dessin sous-jacent dans la peinture. Colloquium X. Le dessin sous-jacent dans le processus de creation, H. Verougstraete and R. van Schoute (eds), Louvain-le-Neuve, 1995, pp. 95–105.

11 M.W. Ainsworth, ‘Some theories about paper and parchment as supports for Early Netherlandish Paintings’, in H. Verougstraete, R. van Schoute and A. Dubois (eds), La Peinture dans les Pays Bas au 16e siècle: pratiques d’atelier, infrarouges et autres méthodes d’investigation, Colloquium, Le Dessin sous-jacent dans la peinture, XII, 1997, Louvain 1999, pp. 251–60.

12 M.W. Ainsworth in Hugo van der Goes: Between Pain and Bliss, (S. Kemperdick and E. Eising (eds), exh. cat., Berlin 2023, pp. 60–61 and 162, no. 14.2, fig. 7, reproduced in colour p. 164 (as attributed to Hugo van der Goes or his circle).

13 The painters Pieter van Coninxloo (fl. 1479–1513), Bernard van der Stockt (before 1469–after 1538), and Jan van Coninxloo I (fl. Brussels, c. 1491), have all been suggested as possible candidates, but all attempts have failed due to lack of sufficient supporting examples or documentation.

14 M.J. Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting, vol. 4, Leiden and Brussels 1969, pp. 59, 90, pl. 104, figs A–C and Add. 161. To these and the portraits cited above may be added further portraits of Adolph of Cleves, c. 1485 (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) and the young Philip the Fair, c. 1492 (Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris). His œuvre was not concentrated exclusively on portraiture, and a series of religious paintings and a single drawing have recently been added to the corpus of his works; see V. Bücken, C. Périer-D’Ieteren, M. Ubl and G. Steyaert, ‘Meester van de vorstenportretten’, in De Erfenis van Rogier van der Weyden. De schilderkunst in Brussel 1450–1520, exh. cat., Brussels 2013, pp. 225–45, nos 43–52.

15 It has been suggested that the portrait of Louis of Gruuthuse (1427–1492), a famous courtier and diplomat at the court of Philip the Good, whose hands are clasped in prayer, formed the right-hand side of a diptych facing an image of the Virgin and Child.

16 Oil on paper laid on canvas, 14.4 x 10. 4 cm.; formerly with Bob Haboldt & Co., New York, Paris and Amsterdam; Périer-D’Ieteren 2015, pp. 19–22, reproduced figs 11a–b.

17 Inv. no. 1975.79.a; oil on oak panel, 28.2 x 19.7 cm.; C. Eisler, The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. Early Netherlandish Painting, London 1989, pp. 130–33, reproduced (as attributed to the Master of the Magdalene Legend).

18 Périer-D’Ieteren 2015, pp. 19–22, figs 11a–b and 12a–b.

19 S. Deprouw-Augustin, ‘Jean Beugier, alias le Maître des portraits princiers, un peintre de la fin du XV siècle entre Amiens, Bruxelles et Bruges’, Revue de l’Art, 208, 2020, pp. 17–29.