To the abstract there should always correspond, like the idea of a thing, something also abstract. What might that be? To be represented graphically, it will either have to be the written name of the thing or a schematic image as far from the apparently real as possible: like a sign.

Painted in 1945 at the height of his mature period, Construcción universal con gran sol presents a culmination of Torres-García’s philosophy and aesthetic vision. After nearly a decade of travel between avant-garde circles in Madrid, Barcelona, and New York, Torres-García settled for a brief but critical period in Paris in 1930, where he founded (alongside Michel Seuphor) the influential group and publication Cercle et carré. Dedicated to a socially utopian approach to geometric abstraction, the group’s philosophical tenets were broad enough to encompass a diverse array of artists ranging from Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian to Kurt Schwitters and Jean Arp. Alongside his dedication to geometry however, Torres-García discovered in Paris two key fonts of visual and spiritual inspiration: Western Medieval art, and pre-Columbian (specifically Inka and Nazca) art and architecture. While Torres-García prized the rational and geometrically pure underpinnings of Neo-Plasticism, he also longed to rekindle the link between the human and the divine that was essential to the creative production of ancient peoples around the world, and which he believed was lost in the modern era. This impulse led to the genesis of Universal Constructivism, which “was the result of Torres-García’s rejection of the pure, nonobjective parameters of Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism on behalf of a form of abstraction that did not exclude the metaphysical or spiritual dimension of art….rather than opt for one approach or the other, Torres-Garcia combined both into a synthesis of form and subject matter contained inside the Neo-Plasticist grid.” (Mari-Carmen Ramirez, “Moving to and from Abstraction Joaquin Torres-Garcia's Uncodified Eclecticism” in Exh. Cat., Houston, Museum of Fine Arts, Intersecting Modernities: Latin American Art from the Brillembourg Capriles Collection, 2013, p.72)

The basis for his constructive-universal articulation was the ‘sign’ - the conflation of visual symbol (form) and idea (content) - that by virtue of its concrete quality was able to convey meaning in a direct, immediate way…. [JTG] classified the signs in three levels: intellectual (geometric figures, numbers, letters, ruler, clock); spiritual (man, woman, cross, temple, zodiac signs, scale, key, ladder, bell); physical (snail, fish, plants, flowers, water). By articulating this basic vocabulary, the artist drew from the vast array of heterogeneous sources that constituted his cultural and intellectual universe: Christianity, Theosophy, Freemasonry, ancient art, as well as the art of children and [sic] primitive peoples. After his final return to Montevideo in 1934, Torres-Garcia incorporated references to the art of Pre-Columbian civilizations. Grounded in the universal experience of mankind, the Constructive-universal signs, nevertheless, suggest a metaphysical dimension…However, the purpose of these signs was to tap into archetypal meanings that cut across cultures and, as such, are buried in mankind’s collective memory. In this way, he created an innovative abstract language that was both concrete and universal in its communicative reach.

Universal Constructivism found few supporters in 1930s Paris, existing as it did in opposition to the dominant camps of Neo-Plasticism and Surrealism, and Torres-García returned to his native Montevideo in 1934. From 1937 onwards, Torres-García was involved in what he termed his “Indo-American project,” concerned with separating Universal Constructivism from its European origins and achieving a uniquely American vision. Construcción universal con gran sol was painted following the founding of the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (AAC) in 1935 and the organization of the Taller Torres-García (TTG) in 1943, whose students included Gonzalo Fonseca, Francisco Matto, Julio Alpuy, and many others. Throughout this period, Torres-García began to incorporate motifs derived from Andean civilizations throughout his works, from the art and architecture of pre-Columbian civilizations, particularly those of the Andes, but also from Mexico and North America, throughout his work. The constructions of this period are rigorously geometric, with emphasis on the organizational grid, made even stronger by the use of subtle shading to create a sense of bas-relief. Another key aspect of these works is their palette, in which primary colors appear but in ruddier, earthier tones —a quality drawn directly from Nazca pottery and aesthetics (see fig. 1).

The dominant image of Construcción universal con gran sol is that of the anthropomorphic sun in the upper center. The extending rays of this figure evokes Inti, the Inka god of the sun, who protected the Inka empire and was believed to be the ancestor of Inka rulers - and who is a key recurring figure in Torres-García’s work of this period. This image harkens the sun deity at the apex of the Tiwanaku Puerta del Sol (the Gate of the Sun), situated at the shore of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia (see fig. 2.) Where in the artist’s earlier works the figure of Inti is rendered in a hieratic, monochromatic and abstracted manner, here the deity appears in rich earth tones with a contented expression. Inti’s rays extend gently outward into the composition and intermingle with the figures of houses, stars, windows, and ladders, suggesting warmth and harmony between the heavens and the earth.

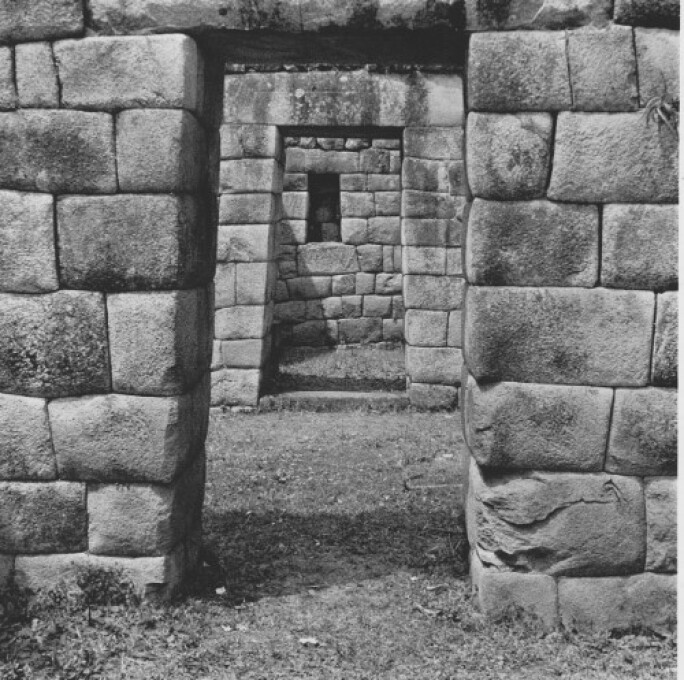

The architectonic balance of the composition overall belies not only Torres-García’s relationship with Neo-Plasticism, but also his fascination with Inka architecture. The Inka fortresses of Sacsayhuamán and Macchu Picchu, with their precision-cut massive stones and geometric portals, would only have been known to the artist through photographs - and yet echoes of the forms of their astounding dry polygonal masonry, constructed entirely of precision-cut massive stones, are clearly visible here in the cascading grid of the composition (see fig. 3). “It is abundantly clear that Torres-Garcia imagined these Inka walls as a form of ancient Constructivism - a kind of “natural” geometry - obeying the laws of orthogonals and tectonics. They also sustain the constructivist notion of basing art on fundamentals in the sense that, as glacial boulders, they were primeval matter.” (Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art in the Post-Columbian World, New York, 2000, p. 259)