“I’ve always loved it. It’s a beautiful painting, the original. It’s in the National Gallery, and I saw it when I was eighteen, when I first went to London... Van Gogh also wrote about the work. What’s fascinating is that, in the painting, there are two vanishing points. One is in the centre of the painting, with the disappearing road. But the other is in the sky. You’re always looking up, because the trees are so tall.”

The National Gallery, London

Image: © Bridgeman Images

Image/Artwork: © David Hockney

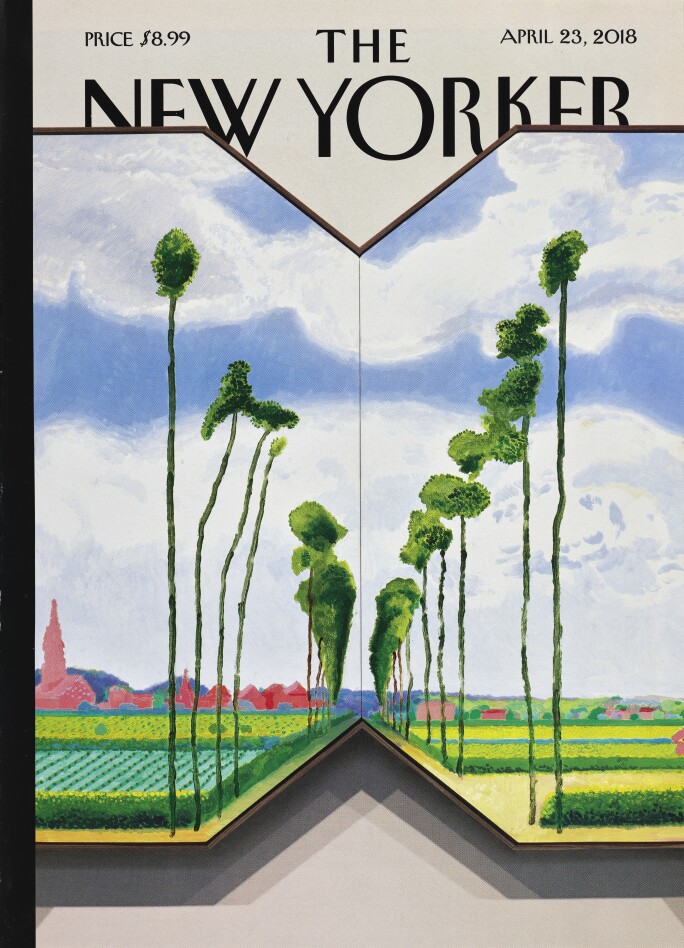

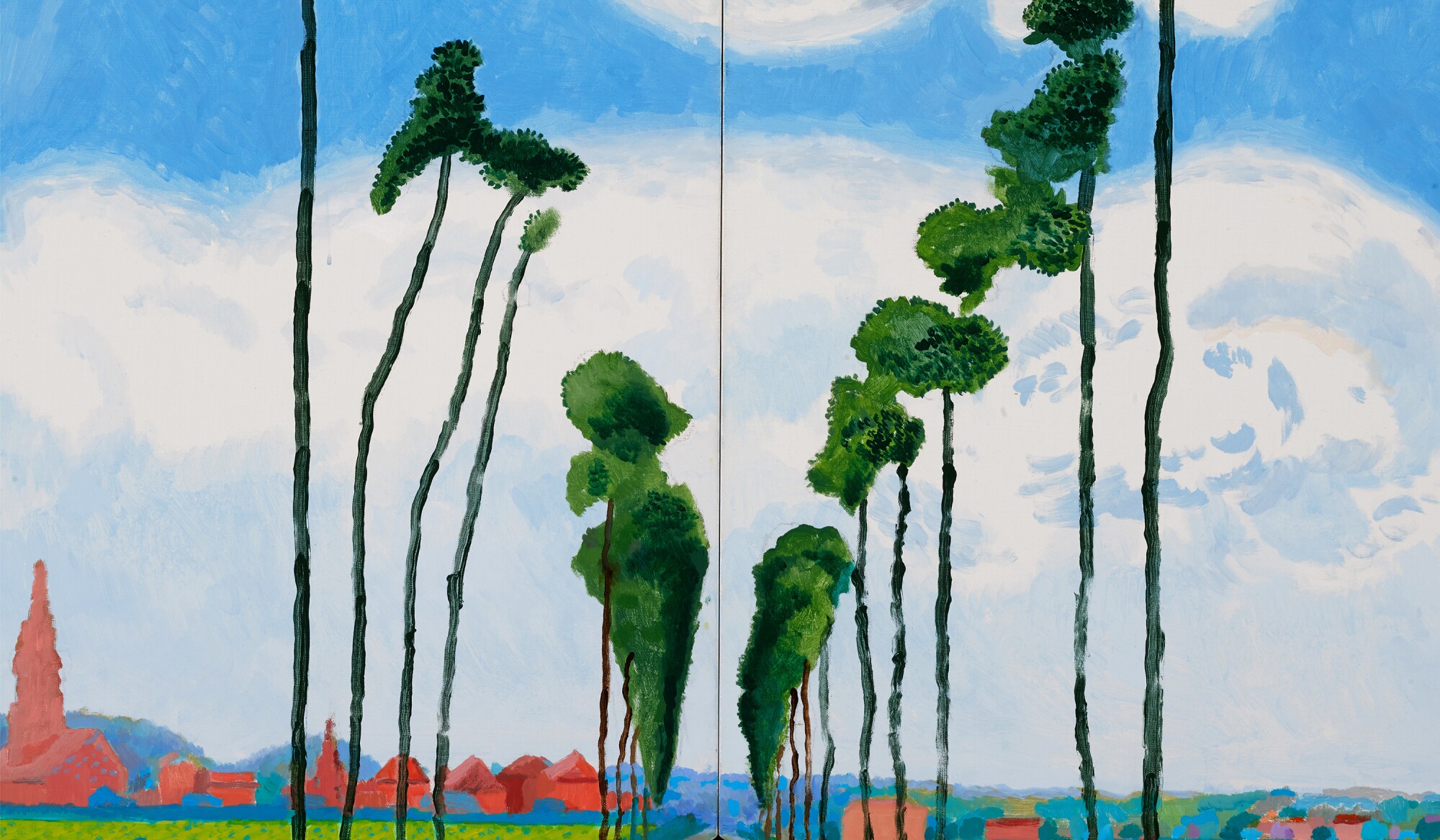

Imbued with a sense of dynamism and sublime vastness, Tall Dutch Trees After Hobbema (Useful Knowledge) 2017 exemplifies David Hockney’s unique, multi-perspectival approach to painting and his visual investigation into a masterpiece of the art historical canon. Executed in 2017, the present work takes its composition from Meindert Hobbema’s celebrated seventeenth-century painting The Avenue at Middelharnis (1689) housed in the National Gallery, London as part of its permanent collection. Here, Hockney translates Hobbema’s conventional European landscape into a saturated, euphoric Californian vista, paying homage to the illustrious original, while radically re-imagining it for a decidedly contemporary audience. Depicted in Hockney’s quintessential graphic vernacular and bold, high-key colour palette, this landscape could be a tree-lined avenue in Beverley Hills, or the sun-drenched slopes of Santa Monica or the Hollywood Hills. Wonderfully reimagined for the 23rd April 2018 cover of The New Yorker, and featured in a large-scale photo-mural Hockney created the same year using an inventive combination of photography and 3D printing, the present work is testament to the artist’s enduring ingenuity and cultural significance in the eighth decade of his life. Executed during Hockney’s renowned 2017-18 retrospective at Tate Britain, London, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Tall Dutch Trees After Hobbema (Useful Knowledge) 2017 transcends the limitations of traditional representation, and disrupts the rigour of conventional perspective via an expansive, bucolic panorama.

Tate Collection, London

Image/Artwork: © David Hockney

The Modern Museum of Art, New York

Image/Artwork: © David Hockney

Hockney’s rendition of Hobbema’s painting is the largest and most exquisite work within a series of twenty late paintings executed in 2017 and 2018, the majority of which are painted on hexagonal or shaped canvases. Throughout the series, Hockney either returned to the subject matter central to his early practice – such as the landscapes of the Hollywood Hills and the Grand Canyon – or he reimagined celebrated compositions of art historical masters, such as Hobbema and Fra Angelico. Indeed, in its reinterpretation of a renowned seventeenth-century landscape, Tall Dutch Trees After Hobbema (Useful Knowledge) 2017 represents the apotheosis of Hockney’s career-long investigation into masterworks of the art historical canon, among them paintings by Vermeer, Hogarth, Monet, Van Gogh, and Picasso. In his profound appreciation of such works, Hockney has executed paintings inspired by – or, less often, directly based on – instantly recognisable historical masterpieces. The present work can thus be compared to a much earlier painting by Hockney of a similar title, Kerby (After Hogarth) Useful Knowledge, executed in 1975. This earlier painting signifies Hockney’s first schematic experiment with perspective, and similarly draws upon art historical source material; the composition is based on a frontispiece illustration by Hogarth to a pamphlet on perspective produced by his friend and artist Joshua Kirby. Like Hobbema before him, Hogarth, too, toyed with perspective, in turn manifesting unique visual effects that would allow the viewer to become an active participant in the scene. Hockney’s 1975 painting now resides in The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in turn solidifying the importance of his art historical investigations.

Hockney’s tendency to draw upon sources from the canon of art history follows a long tradition of contemporary artists looking to the aesthetic language of their predecessors. The present work is reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s Study for ‘Portrait of Van Gogh’ (1957) in the collection of Tate, London; Frank Auerbach’s frenetic interpretation of Ruben’s Samson and Delilah, the original held in the collection of the National Gallery, London, alongside Hobbema’s landscape; or Gerhard Richter’s Verkündigung nach Tizian (Annunciation after Titian), now in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.. Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol’s appropriationist ‘art after art’ style is also of note, yet in the case of the present work, Hockney’s approach radically differs from his Pop art contemporaries in his sincere and intrinsic love of the instructive value of Hobbema’s picture: “I’ve always loved it. It’s a beautiful painting, the original. It’s in the National Gallery, and I saw it when I was eighteen, when I first went to London. I told JP [Hockney’s companion] – just look up Hobbema. He’d never heard of him, we found the painting and made a proof (it was quite good!), and then I painted it. Van Gogh also wrote about the work. What’s fascinating is that, in the painting, there are two vanishing points. One is in the centre of the painting, with the disappearing road. But the other is in the sky. You’re always looking up, because the trees are so tall” (D. Hockney cited in: F. Mouly, ‘David Hockney’s “The Road”’, The New Yorker, 23 April 2018 (online)). Hockney’s exploration of art historical masterworks underscores his theoretical conception of pictorial space in painting – the ultimate expression of which is made manifest on the surface of the present work.

Depicting an idyllic view of a village road in southern Holland, Hobbema’s 1689 painting is comprised of a regimented landscape punctuated by strong vertical lines; tall, lush Alder trees frame the avenue as the viewer’s eye is drawn towards the heart of the composition. The painting illustrates Hobbema’s use of ground-breaking visual devices, and the artist’s early, innovative experiments with perspective. In an essay written for the exhibition catalogue of Hockney’s 2018 Pace show David Hockney: Something New in Painting (and Photography) [and even Printing], during which the present work was debuted, critic and writer Lawrence Weschler explained, “Hockney reached back into his favourites from art history one more time to riff on the Dutch Golden Age landscape painter Meindert Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis – a one-point perspective dazzler if there ever was one – and turned it clean inside-out with a multi-panel extravaganza from which he’d completely filleted the avenue itself, allowing the viewer to peer with a reversed perspective to either side of the now-disappearing road. And then he did the same thing all over again on a grander scale” (L. Weschler, ‘On Not Cutting Corners’, in: Exh. Cat., David Hockney: Something New in Painting (and Photograph) [and even Printing], Pace, New York, 2018, p. 16). Indeed, within this late series Hockney created two versions of Hobbema’s masterpiece; a smaller work entitled After Hobbema (Useful Knowledge) 2017, measuring 112 by 277 centimetres, and the present work – larger and more dynamic – measuring 165 by 368 centimetres.

Image: © Max Lakner/BFA, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Artwork: © David Hockney

The paintings within the concise series to which Tall Dutch Trees After Hobbema (Useful Knowledge) 2017 belongs, are all united by Hockney’s highly nuanced and considered use of reverse perspective. The very same year the present work was executed, Hockney discovered a ground-breaking essay from 1920 entitled Reverse Perspective by Pavel Florensky, a mathematician, art critic and aesthetic theorist: “Florensky, like Hockney after him, pointed out that we ourselves never ever see in rigorously abstracted perspective (the way a camera does) because, for starters, we look out at the world binocularly, from two eyes simultaneously, and for that matter, our eyes and bodies are always in motion, as we construct our actual sense of the world across time from all those multiple vantages” (L. Weschler cited in: Ibid., p. 11). Hockney’s version of Hobbema’s classical landscape thus problematises the use of one-point perspective while presenting an enduring interrogation of the issues of representation. The artist himself asserts, “If you’re going through a tunnel, when you get out, everything opens up. That’s reverse perspective. The problem with perspective is this: you’re an immobile point, here, outside the picture. But, with reverse perspective, you can be a moving person – you can see all sides of things from a single point. And we’re always in movement. The eye is always in movement. It’s never still. Cubism, for example, was really an attack on perspective” (D. Hockney cited in: op. cit.,).

Image: © Tom Barratt, courtesy Pace Gallery

Artwork: © David Hockney

A pivotal moment in Hockney’s early investigations into the power of reverse perspective occurred in 1985 when travelling by car between Milan and Zurich. Hockney and a friend drove by way of the Gotthard Road Tunnel, and in the tunnel Hockney described his view as, “unobstructed all the way down to the tiny pinprick of light in the far far distance, all the lines of sight converging relentlessly on that tiny dot, endlessly, for minutes on end… suddenly I realised how that is the basis of all conventional photographic perspective, that endless regress to an infinitely distant point in the middle of the image, how everything is hurtling away from you and you yourself are not even in the picture at all. But then, as we got to the end of the tunnel, everything suddenly reversed, with the world opening out in every direction. The effect was fantastically invigorating, you suddenly felt yourself at the focal point of vantages spreading out in every direction. And I realised how that, and not its opposite, was the effect I wanted to try to capture” (D. Hockney cited in: L. Weschler ‘On Not Cutting Corners’, in: Exh. Cat., New York, Pace, David Hockney, 2018, p. 5-6). By subverting the superiority of one-point perspective, Hockney found he was able to more vigorously explore the viewer’s experience of binocular looking, and seemingly integrate the viewer into the scene.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Image: © 2021 The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

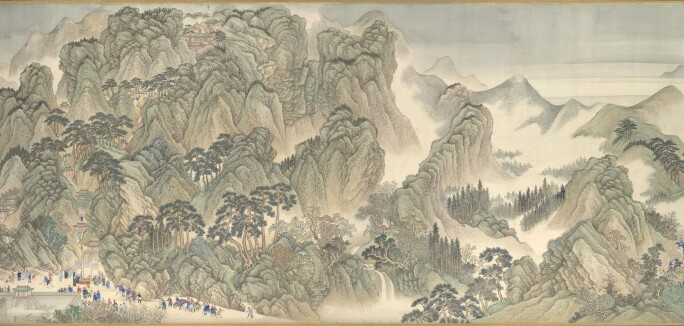

Another critical reference point in unpacking Hockney’s late experiments with perspective is Chinese scroll painting, the influence of which is palpable on the surface of the present work. In 1984, Hockney made numerous visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where he saw Chinese scroll paintings for the first time. During this period, he came across George Rowley’s 1947 book The Principles of Chinese Painting, in which Rowley argued that Chinese scroll painting, “re-worked the early principles of time and suggested a space through which one might wander and a space which implied more space beyond the picture frame. We restricted space to a single vista as though seen through an open door; they suggested the unlimited space of nature as though they had stepped through that open door and had known the sudden breath-taking experience of space extending in every direction and infinitely into the sky” (G. Rowley cited in: Ibid., p. 146). Rowley’s words mirror Hockney’s own description of the remarkable effects of reverse perspective, and his feeling of wonder as he exited the Gotthard Road Tunnel in 1985. As Weschler asserted upon viewing Hockney’s late series of paintings during a visit to the artist’s studio in 2017, “This was not so much reverse perspective as moving focus (albeit spread across an airy and well-ventilated reverse perspectival expanse), the sort of thing he grew to appreciate during his immersion in Chinese scrolls, where the latter of locally specific schemes (blended across the wider expanse) enforced in the viewer an experience of slower time and sequentially parceled attention” (L. Weschler cited in: Op. cit., p. 17). Indeed, the aesthetics of Chinese scroll painting presented Hockney with radical possibilities in rendering time, space and movement across the two-dimensional surface of a canvas, possibilities which are spectacularly embodied by present work.

David Hockney on Vincent van Gogh | FULL INTERVIEW

-

Contemporary ArtFinding Purpose in Art, Identity & the Ocean: In The Studio with Otis Hope Carey

Contemporary ArtFinding Purpose in Art, Identity & the Ocean: In The Studio with Otis Hope Carey -

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story

Sotheby's StoriesHow Jane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Made History... Again | A Sotheby's Auction Story -

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's

Handbags & FashionJane Birkin's Original Hermès Birkin Bag Shatters Auction Records at $10.1 Million | Sotheby's

Executed in the eightieth year of the Hockney’s life, Tall Dutch Trees After Hobbema (Useful Knowledge) 2017 is a recent and outstanding example of the artist’s beloved style of landscape painting. With its bold hues of turquoise, cerulean, coral and green, the present work translates Hobbema’s painting into a bright and theatrical composition quintessential to Hockney’s celebrated oeuvre. Here, the shape of the canvas poignantly visualise the very nature of our own binocular vision: “… I’ve begun to wonder lately whether one reason Hockney’s notched hexagons feel so somehow right, or at any rate seem to evoke the phenomenological feel of one’s actual depth of field, is that they are in fact mimicking the way we actually see…” (L. Weschler cited in: Ibid., p. 15). The present work illuminates a winding, disappearing road, the cut in the canvas on the lower edge perhaps also alluding to the hood of a car. Many of Hockney’s most important landscapes are depicted from the vantage point of car, and these canvases are imbued with the artist’s fond memories of driving through the Hollywood Hills, the Grand Canyon, or the countryside of East Yorkshire. Thus the present work signifies a vividly contemporary take on Hobbema’s picture. A rich amalgam of different eras and places, a fusion of old and new, the present work is an immersive, temporal landscape which Hockney’s viewers seem to move through at speed: “Using actually observed landscapes, [Hockney] sought to describe in paint the physical and visual experience of being in and moving through wide, open, deep spaces, bringing together a dynamic point of view, multiple perspectives and horizons” (C. Stephens cited in: Exh. Cat., London, Tate Britain (and travelling), David Hockney, 2017-18, p. 161).