These characterful and brilliantly-colored panels of four saints are important works in the small but distinctive œuvre of the Master of Eggenburg, an anonymous artist active in and around Lower Austria in the last quarter of the fifteenth century. The panels originally formed part of the exterior wings of a large altarpiece dedicated to the life of Wenceslas (907–935), a Bohemian Duke of the Přemyslid dynasty who was venerated for his just rule and piety later and later became a patron saint of the Czech lands. While the exact details surrounding this altarpiece and its commission remain unknown, at least eight other related panels from this retable survive today. Of them, two are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and six others are in the National Gallery of Prague.

Wenceslas appears upon one of these two panels as a warrior in armor, crowned and wielding a shield and banner with his symbol, the black eagle (or “flaming eagle”), which remains part of the Czech coat of arms to this day. Beside him stands his grandmother, Ludmila of Bohemia (c. 860–921), canonized after her assassination by her daughter-in-law Drahomíra, Wenceslas’ mother, who resented Ludmila’s influence over her son. After Wenceslas came of age in 922, Drahomíra was exiled but succeeded in turning her younger son, Boleslav, against his older brother. Boleslav orchestrated Wenceslas’ murder in September 935 during the feast of Saints Cosmas and Damian in Stará Boleslav. As recorded in the Historiae Regni Boiemiae (Prostějov 1552), Boleslav initially buried Wenceslas’s body there but later moved it to the Prague Cathedral dedicated to Saint Vitus in hopes that miracles taking place at Wenceslas’ grave would be associated with Vitus instead. Wenceslas, though, was venerated as a martyr almost immediately following his death, with several biographies of the righteous king (a title conferred on him posthumously) in circulation within a few decades of his demise. Furthermore, his feast day—28 September—was established as early as 984.

The aforementioned Saint Vitus, venerated throughout Prague and the Slavic lands, appears on the other panel as a young man with curly blonde hair, wearing a crown and an elegant red cloak, while holding an orb in his right hand and the palm of his martyrdom in the left. Of Sicilian birth, Vitus was a devout Christian who lived in the third or fourth century. Among his many miracles, he emerged unharmed from a cauldron of boiling tar while enthusiastically dancing, securing him as the patron saint of dancers. In 925, Emperor Henry I gifted a holy relic of Saint Vitus to Wenceslas, inspiring Wenceslas to build the foundation of St. Vitus Cathedral and establishing the saint’s veneration in Prague. Later, in 1355, Charles IV brought additional relics of Vitus to the cathedral, which soars over the skyline of Prague to this day. Although the inscription in the halo of the saint to the right of Saint Vitus identifies him as Saint James the Greater, it seems more likely that this is Saint James the Lesser rather than the saint who is often shown wearing a hat and holding a pilgrim's staff and a shell. The saint here is shown with what seems to be a hatter’s bow (a tool used to clean the wool used in hats), an attribute popular for James the Lesser in Germany from the 14th century onwards, as well as two pieces of bread, possibly symbolic of his fast until Christ’s resurrection.

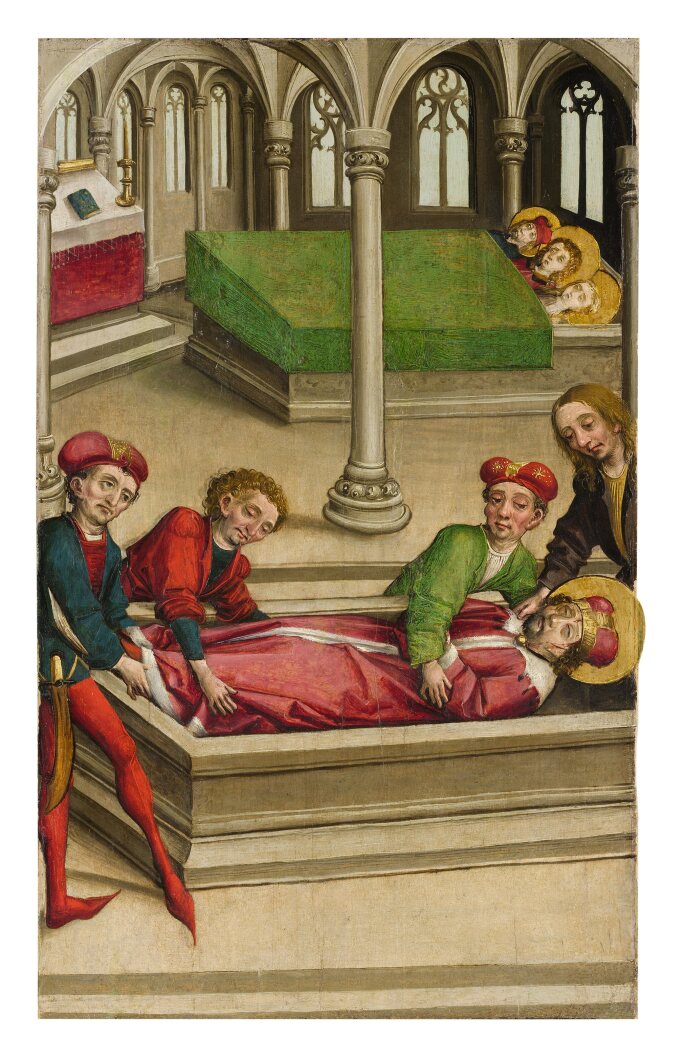

The other known surviving panels from this altarpiece similarly depict saints, which would have formed part of the outer wings, or narrative episodes from Saint Wenceslas’ life, which would have adorned the interior of the wings. Notably, two panels from the altarpiece are today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. One panel portrays Saints Adalbert and Procopius (fig. 1), while the other illustrates The Burial of Saint Wenceslas (fig. 2).1 Six additional panels, today in the National Gallery in Prague, all represent scenes of Saint Wenceslas: Saint Wenceslas Liberating the Prisoners, Saint Wenceslas Regaling Pilgrims in Stará Boleslav, Saint Wenceslas Collecting Firewood for the Poor and being Tortured by Gamekeepers, Saint Wenceslas Led by Angels and Welcomed by King Henry I the Fowler at Reichstag, The Martyrdom of Saint Wenceslas and The Securing of the Body of Saint Wenceslas.2

Featured in the upper right corner of the panel depicting Saint Wenceslas Liberating the Prisoners are three coats-of-arms associated with Bohemia and Moravia—the latter being the former margravate in which the Master of Eggenburg is believed to have been active. These heraldic elements may offer a clue as to the altarpiece’s original commission, although no more precise identification has yet been established. Furthermore, the precise arrangement and scope of the original altarpiece remain uncertain; it is unclear whether the altarpiece was composed entirely of painted panels or if it featured a sculpture of Saint Wenceslas at the center. Moreover, given that episodes from the saint’s life recorded number as many as twenty-nine, the overall assemblage may originally have been considerably larger than the surviving elements suggest.

The altarpiece from which these panels originate has long been attributed to the Master of Eggenburg, whose body of work was first defined in 1932 by Otto Benesch.3 He identified this anonymous artist as a pupil of the Master of Herzogenburg, a late 15th-century painter active in Lower (or Northern) Austria, specifically in Gars am Kamp in the Waldviertel region, where he worked in 1491. Benesch assembled a modest but significant œuvre for the master around a central work: an altarpiece panel of The Death of the Virgin commissioned for the Lower Austrian Redemptoristenkloster in Eggenburg, just south of Moravia.4 Subsequent art-historians, including Bodo Brinkmann and Olga Kotková, have furthered the research on the Master of Eggenburg. Brinkmann, for example, has instead proposed this artist was a contemporary rather than a pupil of the Master of Herzogenburg, noting general rather than specific stylistic affinities to the latter Master’s Last Supper of 1491 in the Heiligenkreuz Stiftsmuseum.5

The Master of Eggenburg’s style is distinguished by a sculptural quality, evident in both the underdrawing and the painted surface. His approach is characterized by the use of distinct, gradated areas of color to construct volume, as seen in the green robes of Saints Ludmila and James the Minor. The artist appears to have a particular affinity for red accents, which frequently appear in his works. Atop these often-opaque areas of color, the Master of Eggenburg uses precise light and dark strokes to denote form, most notably here in the flesh tones of the figures. These figures are marked by large, rather hooded eyes and prominent cheek bones, all features that recur throughout his œuvre. A hallmark of his style is the vibrancy and vigor of his execution, achieved in part by his minimal use of glazes, as exemplified in the present panels.

In addition to the panels from the Wenceslas altarpiece and the Master’s eponymous work, The Death of the Virgin, in Eggenburg, Otto Benesch attributed several other works to this artist’s distinctive hand. Among these are four panels from an altarpiece dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, including one panel illustrating the Saint’s beheading today in the Städel Museum, Frankfurt (fig. 3).6 Benesch also identified a Last Supper, possibly also from the Eggenburg altarpiece,7 and an illuminated missal sheet that featured a Crucifixion.8 Building on Benesch’s original attributions, Bodo Brinkmann has added a fragment of a female saint in a private collection,9 and Olga Kotková has attributed to the Master a panel of Saints Bonaventura and Anthony in the Diözesanmuseum in Vienna.10

1 Respectively, inv. no. 44.171.1 and inv. no. 44.147.2; see Ainsworth 2013, pp. 201-205, cat. nos. 48A, 48B, reproduced.

2 Respectively, inv. no. O 11908 (70 by 45.8 cm), inv. no. O 11909 (68 by 44.5 cm), inv. no. O 1483 (68.5 by 42.5 cm), inv. no. O 1257 (69.7 by 43.5 cm), inv. no. O 1484 (68 by 44 cm), and inv. no. O 1256 (69.3 x 43.5 cm); see O. Kotková, Illustrated Summary Catalogue. Old European Art, German and Austrian Painting of the 14th-16th Centuries. National Gallery in Prague, Prague 2007, pp. 106-109, cat. no. 57, all reproduced. While these panels are all today in the National Gallery in Prague, their provenance differs: two were acquired in 1939 from the Konopiště State Castle in 1939, two were acquired from the legacy of Bishop Dr. Antonín Podlaha, and two were purchased in 1921 from the Galerie St. Lucas in Vienna.

3 O. Benesch, "Der Meister des Krainburger Altars," in Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 8 (1932), pp. 27-28.

4 Mixed media on panel, 70 by 42 cm, see H. Tietze, “Die Denkmale der Gerichtsbezirke Eggenburg und Geras,” in Die Denkmale der politischen Bezirkes Horn in Niederösterreich, vol. V, part I, Vienna 1911, pp. 39-40, reproduced fig. 38.

5 Inv. no. GE219-1, oil and tempera on panel, 142 by 115 cm; see B. Brinkmann, in Deutsche Gemälde im Städel, 1300-1500, Mainz 2002, pp. 280-281, the Last Supper reproduced p. 278, fig. 248.

6 Inv. no. 1621, mixed media on spruce panel, 60.3 by 45.5 cm. The other three panels include Zacharias Writing the Name of John the Baptist andThe Baptism of Christ, both of which were auctioned in Munich in 1984, as well as The Preaching of Saint John the Baptist, formerly in the Berlin collection of Harry Fuld; see Brinkmann 2002, p. 276, all three reproduced figs 241-243.

7 Mixed media on panel, 69 by 41 cm, anonymous sale, Vienna, Dorotheum, 13-15 May 1929, lot 35.

8 Stiftsbibliothek Geras b. Horn, fol. 243v; see Brinkmann 2002, p. 279, reproduced fig. 249.

9 Brinkmann 2002, pp. 280-281, reproduced fig. 251.

10 Kotková 2007, p. 106.