“I would call it attitude, you know, the way that you can make something almost talk by the way the neck is bent, or the attitude of the head; you can actually make these sculptures talk, they say something according to the exact balance…”

The present work is a monumental version of Chadwick’s most iconic theme: standing and seated figures. It forms the apex of his figurative work in which he investigates the relationships between his figures, in this case juxtaposing three female figures. Chadwick explores the physical and psychological interpersonal dynamic, highlighting both the possible tension and harmony between them. This constant conflict is often expressed in terms of balance: “In the mobiles you have the arm, and you balance two things on it like scales—you have a weight at one end and an object at the other end. If you have a heavy weight close to the fulcrum then you can have a light thing at the other end. So you can [similarly] balance the visual weight of [...] objects” (L. Chadwick quoted in D. Farr, Lynn Chadwick, London, 2003, p. 98).

This juxtaposition yet co-dependence is only further amplified by the artist’s choice of materials and handling of texture, of which the present work is a particularly exemplary work. Chadwick had no formal training as a sculptor but his background in architecture and design provided a strong affinity with materials and the ability to manipulate them to create a variety of desired effects. Once he began to work on large scale works, he completed a welding course to shape and create monumental pieces in a wide range of techniques. As a result, the 1960s saw a turning point for the artist with the introduction of polished facets to his works, most notably in the Elektra series. The resulting contrast between the highly polished bronze and roughly textured metal demonstrates the artist’s ingenious and playful use of materials and a turn towards more naturalistic elements. Similarly, the soft rendering of the female’s upper torso introduces an anthropomorphic element previously lacking from the artist’s work, and further enhances the contrast to his formerly characteristically stylized, geometric forms.

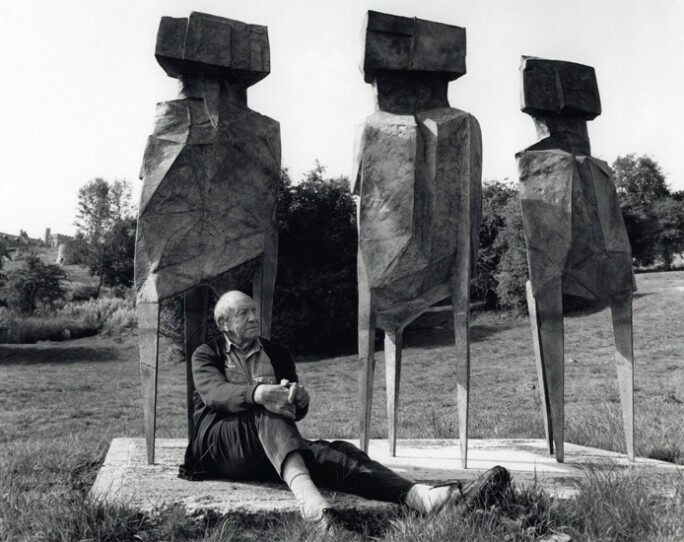

This move towards the anthropomorphic can already be felt in the monumental series of The Watchers (see fig. 2) dating from the early 1960s. While these figures still clearly hark to Chadwick’s earlier more rigid and angular aesthetic, there is a growing sense of interaction and intimacy between the figures. As Collette Chattopadhay writes of the lyrical potency of these compositions: “A new fondness for naturalism begins to appear in Chadwick's work which endows his geometric figures with a startling anthropomorphic credibility. The angle at which a geometric head tilts, or the manner in which a cubic torso leans forward or sideways, imbues these robotic creatures with an uncanny familiarity. Indeed, Chadwick's propensity for infusing cubic figures with ironic, anthropomorphic allusions remains one of his supreme artistic accomplishments, vying with and at times surpassing Picasso's explorations in these areas” (C. Chattopadhay in Exh. Cat., Los Angeles, Tasende Gallery, Lynn Chadwick, 2002, p. 7).

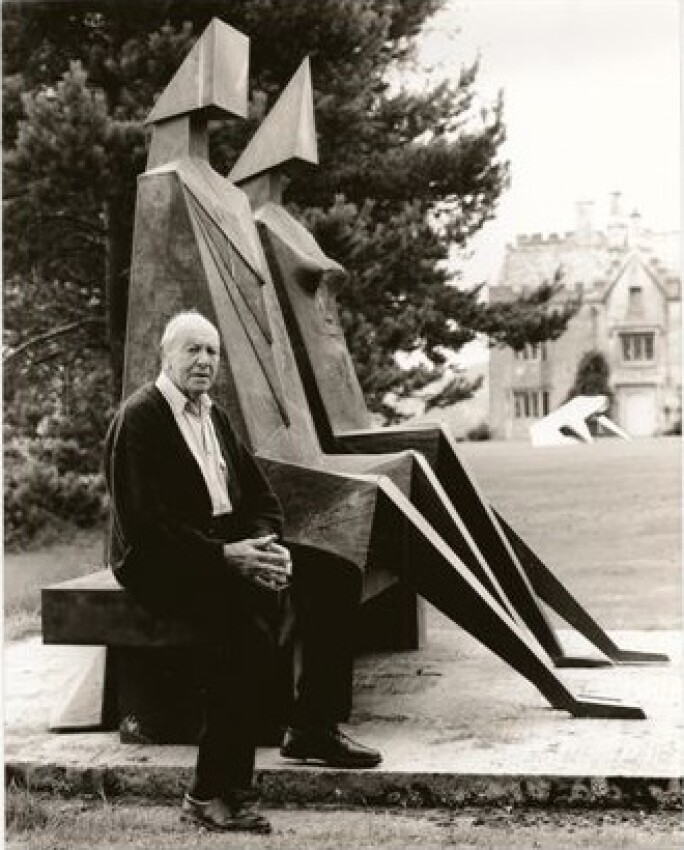

Lynn Chadwick was propelled to fame in 1952 as one of the seven young British Sculptors included in the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of that year. Curated by Herbert Read, it was in his catalogue introduction for this exhibition that Read coined his famous phrase, “the geometry of fear,” to describe the nature of both abstract and figurative sculpture included in the show. The group of artists that included Chadwick, Eduardo Paolozzi, William Turnbull, Reg Butler, Robert Adams, Kenneth Armitage, Geoffrey Clarke, and Bernard Meadows signaled the emergence of a new generation of British artists onto the international stage. These sculptors were seen by Read to manifest post-war angst: "These new images belong to the iconography of despair, or of defiance; and the more innocent the artist, the more effectively he transmits the collective guilt. Here are images of flight, or ragged claws 'scuttling across the floors of silent seas,' of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex, the geometry of fear” (H. Read in Exh. Cat., British Council, XXVI Biennale di Venezia, 1952). Four years later Chadwick was chosen as the sole British representative for sculpture at the 1956 Venice Biennale (see fig. 3) and cemented his international reputation by winning the International Sculpture Prize, ahead of well established artists such as Alberto Giacometti and César. Not only did it propel Lynn Chadwick to artistic fame but also cement his legacy as a successor to Henry Moore as Britain's leading sculptor and artistic ambassador.

An exciting and dynamic character, the Elektra figure was created in a number of variations, including individual forms that are alternately sitting or reclining, unpolished and typically much smaller in scale. Created in an edition of four, other casts of Three Elektras are found in the collection of the Uehara Museum in Japan as well as that of the University of Gloucestershire. The Chadwick heirs have kindly confirmed that the sculptures were executed in 1969 and erroneously stamped ‘68.’