- 42

Norman Rockwell

Estimate

5,000,000 - 7,000,000 USD

Log in to view results

bidding is closed

Description

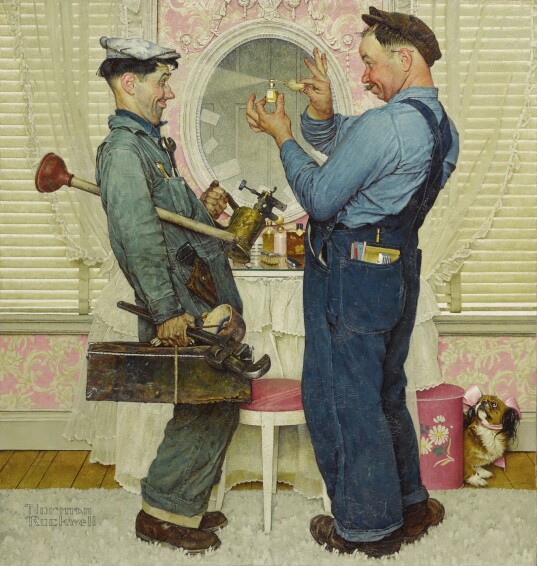

- Norman Rockwell

- Two Plumbers

- signed Norman Rockwell (lower left)

- oil on canvas

- 39 1/4 by 37 inches

- (99.7 by 94 cm)

- Painted in 1951.

Provenance

Gordon Andrew

Bernard Danenberg Galleries, New York

Ernest Schwartz Trust, 1972 (acquired from the above; sold: Sotheby's, New York, May 22, 1996, lot 116, illustrated)

Acquired by the present owner at the above sale

Bernard Danenberg Galleries, New York

Ernest Schwartz Trust, 1972 (acquired from the above; sold: Sotheby's, New York, May 22, 1996, lot 116, illustrated)

Acquired by the present owner at the above sale

Exhibited

Fort Lauderdale, Florida, The Fort Lauderdale Museum of the Arts; Brooklyn, New York, Brooklyn Museum; Washington, D.C., Corcoran Gallery of Art; San Antonio, Texas, Marion Koogler McNay Institute; San Francisco, California, M.H. de Young Memorial Museum; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Oklahoma Art Center; Indianapolis, Indiana, Indianapolis Museum of Art; Omaha, Nebraska, Joslyn Art Museum; Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, Norman Rockwell: A Sixty Year Retrospective (organized by Bernard Danenberg Galleries, New York), February 1972-April 1973, illustrated p. 112

Literature

The Saturday Evening Post, June 2, 1951, illustrated on the cover ©SEPS licensed by Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN. All rights reserved

Thomas Buechner, Norman Rockwell: Artist & Illustrator, New York, 1970, illustrated pl. 483

Christopher Finch, Norman Rockwell's America, New York, 1975, illustrated no. 283, p. 221

Dr. Donald Stoltz and Marshall L. Stoltz, Norman Rockwell and 'The Saturday Evening Post:' The Later Years, New York, 1976, vol. II, pp. 101, 173, illustrated pp. 102, 138

Mary Moline, Norman Rockwell Encyclopedia: A Chronological Catalog of the Artist's Work (1910-1978), Indianapolis, Indiana, 1979, illustrated fig. 1-376, p. 77

Susan E. Meyer, Norman Rockwell's People, New York, 1981, p. 102, illustrated in color p. 103

Laurie Norton Moffatt, Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue, Stockbridge, Massachusetts, 1986, vol. I, no. C456, p. 186, illustrated p. 187

Gregg De Young, "Norman Rockwell and American Attitudes Toward Technology," Journal of American Culture, Spring 1990, p. 102, illustrated fig. 8

Jan Cohn, Covers of "The Saturday Evening Post:" Seventy Years of Outstanding Illustration from America's Favorite Magazine, New York, 1995, illustrated p. 231

Ron Schick, Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, New York, 2009, p. 110, illustrated

The Saturday Evening Post: Norman Rockwell Special Collector's Edition, vol. I, no. I, 2010, illustrated p. 114

Thomas Buechner, Norman Rockwell: Artist & Illustrator, New York, 1970, illustrated pl. 483

Christopher Finch, Norman Rockwell's America, New York, 1975, illustrated no. 283, p. 221

Dr. Donald Stoltz and Marshall L. Stoltz, Norman Rockwell and 'The Saturday Evening Post:' The Later Years, New York, 1976, vol. II, pp. 101, 173, illustrated pp. 102, 138

Mary Moline, Norman Rockwell Encyclopedia: A Chronological Catalog of the Artist's Work (1910-1978), Indianapolis, Indiana, 1979, illustrated fig. 1-376, p. 77

Susan E. Meyer, Norman Rockwell's People, New York, 1981, p. 102, illustrated in color p. 103

Laurie Norton Moffatt, Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue, Stockbridge, Massachusetts, 1986, vol. I, no. C456, p. 186, illustrated p. 187

Gregg De Young, "Norman Rockwell and American Attitudes Toward Technology," Journal of American Culture, Spring 1990, p. 102, illustrated fig. 8

Jan Cohn, Covers of "The Saturday Evening Post:" Seventy Years of Outstanding Illustration from America's Favorite Magazine, New York, 1995, illustrated p. 231

Ron Schick, Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, New York, 2009, p. 110, illustrated

The Saturday Evening Post: Norman Rockwell Special Collector's Edition, vol. I, no. I, 2010, illustrated p. 114

Condition

Please contact the American Art department for this condition report: (212) 606 7280 or americanart@sothebys.com

In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective qualified opinion.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING CONDITION OF A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD "AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF SALE PRINTED IN THE CATALOGUE.

In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective qualified opinion.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING CONDITION OF A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD "AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF SALE PRINTED IN THE CATALOGUE.

Catalogue Note

Humor is a word frequently associated with the work of Norman Rockwell. Over the course of his nearly 50-year association with The Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell made Americans slowly smile, chuckle to themselves, or even laugh aloud through the ceaselessly creative images he conceived for the cover of this widely popular magazine. These commissions continue to attest to the artist’s unparalleled ability to capture moments of everyday life in America with his distinctive warmth and wit. Indeed, it is easy to find the humor in Rockwell’s work, often because the situation he depicts is something we have experienced ourselves. Though a generation of Americans all likely have their own favorite Rockwell, Two Plumbers is undoubtedly among his most beloved images. Painted at the height of the artist’s career, it represents the very best of Norman Rockwell: a work that is seemingly simple in subject yet extraordinarily complex in design and execution and maintains its charm and appeal even today.

Appearing on the cover of The Post on June 2, 1951, Two Plumbers is among the most overtly comedic images the artist created for the publication (Fig. 1). Here Rockwell depicts two rough-and-tumble plumbers sent to attend to the pipes in an unseen bathroom. Dressed for the task at hand and still holding the tools of their trade, the plumbers have discovered a frilly boudoir, ornately decorated in a symphony of ruffles and shades of pink. Intrigued by the array of the unfamiliar yet tantalizing objects on the table, their curiosity gets the best of them and—professionalism thrown aside—one sprays his partner with what is undoubtedly expensive perfume. The owner of the home has not yet returned but the room is guarded by a small lapdog that watches the intruders suspiciously, reinforcing the idea that they have happened upon a place where they truly do not belong.

By the year he painted Two Plumbers, Rockwell had achieved a pervasive level of popularity in the United States. Of the 321 images he painted for The Post between 1916 and 1963, well over 100 were executed during the 1940s and 1950s—the period now considered his most important—as he crafted increasingly ambitious compositions that were highly sophisticated in message and tone. He became regarded as a master storyteller, receiving particular praise for his ability to conjure the elements of multifaceted narrative into a single image. “When painting a Post cover,” Rockwell stated, “I must tell a complete, self-contained story. An illustration is merely a scene from a story” (quoted in Virginia Mecklenburg, Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, New York, 2010, p. 86).

The impressive sense of naturalism that Rockwell achieved in works from this period including Two Plumbers was achieved in large part through his complex technical process, which he developed and refined throughout the early decades of his career. The 1930s introduced two particularly important changes in his working method. Encouraged by a younger generation of artists that included Steven Dohanos and John Falter, Rockwell began to experiment with photography in 1937. Only after painstakingly collecting the appropriate props, choosing his desired models and scouting the perfect location would photography sessions begin, both on site and in his studio. Rockwell rarely took these photographs himself, preferring to be free to adjust each element while a hired photographer captured images under his direction.

Concurrently, Rockwell also began to rely solely on his friends and neighbors in his new home of Arlington, Vermont, to serve as his models. Living in working-class New Rochelle, New York, had previously required the artist to depend largely on children to serve as models as the majority of the adult population could not spare the long stretches of idle time required to sit for the artist. When he did paint adults, Rockwell employed professional models, a reliance he came to believe hindered the degree of authenticity his work could achieve. However, Rockwell found the opposite in Arlington: a plethora of neighbors of all ages willing to model for him. “Now my pictures grew out of the world around me,” the artist described of this important change, “the everyday life of my neighbors. I don’t fake it anymore” (quoted in Susan E. Meyer, Norman Rockwell’s People, New York, 1981, p. 64).

Two of Rockwell’s studio assistants, Don Winslow and Gene Pelham, modeled for the central characters in the present work, posed in front of a dressing table owned by Mary Rockwell, the artist’s wife (Fig. 3). The artist recognized the benefits that came from utilizing the camera, particularly when his composition included an animal. Images of animals appear frequently throughout Rockwell’s body of work, as the artist often utilized them to visually reinforce his message and tone. In 1954’s Breaking Home Ties, for example, the inclusion of the family collie reinforces the tenderness of this scene of a young man saying goodbye to his hometown and childhood (Fig. 4). Indeed, Rockwell never added an animal to a composition merely to add to its popular appeal. “It takes much kindness and patience to handle animal models,” he once explained, “but the effort is worthwhile because they are so often important elements in story telling pictures…. I do not like to see an appealing animal put into a picture just to save a job. This trick does not fool anyone. I never include an animal in any picture unless it seems natural for it to be in the setting. But when you have a scene in which animals might be expected to appear, paint them well and put them in because people love to see them” (Rockwell on Rockwell: How I Make a Picture, New York, 1979, p. 108) (Fig. 5).

Indeed, the apparent veracity captured in Two Plumbers belies the careful deliberation with which Rockwell executed this and all of his most successful works. The artist’s perfectionism was infamous; he included every element to serve a specific purpose and often created numerous sketches and studies before executing the final version of the painting (Fig. 2). In Two Plumbers, the dog at the lower right serves as an important compositional device. Like many of the supporting players in the artist’s most complex paintings, the dog represents, “a character within the painting’s space whose response to the action we may take as a cue to our own response and through whose eyes we are presumed to see the scene portrayed in its optimum configuration” (Dave Hickey, “The Kids Are Alright: After the Prom,” Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, New York, 1999, p. 119). As Hickey notes, the addition of the dog references a technique of 18th century French painting as exemplified by Jean Honoré Fragonard’s, The Swing, in which the man lounging in the bushes has a revealing view of the swinging woman that the viewer is not granted, yet we know from his expression and reaction that the artist intended for the tone of the work to be humorous (Fig. 6). In Two Plumbers, the worried eyes of the Pekingese underscore the idea that the men are trespassing, which in turn makes us as the viewers complicit in the affair as we watch and laugh but do nothing to stop them.

Rockwell enjoyed referencing other well-known works of art in his own paintings, as it provided the type of visual game that the artist loved to present to his viewers. Rockwell also used these allusions to demonstrate his deep knowledge of art historical precedents. In Two Plumbers, the central figures form an inverted triangle, mimicking a pictorial configuration often employed by the painters of the Italian Renaissance and creating the impression of stability within the composition. The strong horizontality of the window blinds and baseboard is countered by the verticality of the figures, creating a geometric grid onto which Rockwell could add the ornate details of the extravagantly decorated room without sacrificing the harmonious compositional balance of the scene.

The enduring popularity of images like Two Plumbers speaks to Rockwell’s ability to select subjects that appealed almost universally to American audiences, and to uniquely infuse his compositions with compelling elements of comedy. “It is easy to see that had he not been a gifted artist,” stated his biographer Christopher Finch, “Norman Rockwell might well have become a successful writer or director for film or television. Situation comedy has been one of the most popular genres in both these mediums, and no one has a better knack for inventing comic situations than Rockwell” (102 Favorite Paintings by Norman Rockwell, New York, 1978, p. 124). Rockwell was fascinated with television, and by the 1950s, he regularly mined the new medium for source material. Nowhere is this clearer than in Two Plumbers, where the humorous adventures of the plumbers seem a direct allusion to the slapstick antics of the comedy team of Laurel and Hardy, who enjoyed the height of their popularity in America during the 1930s and 1940s (Fig. 7).

Rockwell painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post in 1916, and his last in 1963. While he never abandoned the subtly nostalgic and persistently optimistic aesthetic that made him beloved by Americans and his work instantly recognizable as his own, the subjects he addressed changed over time to reflect the country’s evolving cultural, social and political mores. Ultimately, works such as Two Plumbers not only demonstrate Rockwell’s rare gift for storytelling, but also the genius with which he kept a massive and diverse audience engaged for more than half a century.

Appearing on the cover of The Post on June 2, 1951, Two Plumbers is among the most overtly comedic images the artist created for the publication (Fig. 1). Here Rockwell depicts two rough-and-tumble plumbers sent to attend to the pipes in an unseen bathroom. Dressed for the task at hand and still holding the tools of their trade, the plumbers have discovered a frilly boudoir, ornately decorated in a symphony of ruffles and shades of pink. Intrigued by the array of the unfamiliar yet tantalizing objects on the table, their curiosity gets the best of them and—professionalism thrown aside—one sprays his partner with what is undoubtedly expensive perfume. The owner of the home has not yet returned but the room is guarded by a small lapdog that watches the intruders suspiciously, reinforcing the idea that they have happened upon a place where they truly do not belong.

By the year he painted Two Plumbers, Rockwell had achieved a pervasive level of popularity in the United States. Of the 321 images he painted for The Post between 1916 and 1963, well over 100 were executed during the 1940s and 1950s—the period now considered his most important—as he crafted increasingly ambitious compositions that were highly sophisticated in message and tone. He became regarded as a master storyteller, receiving particular praise for his ability to conjure the elements of multifaceted narrative into a single image. “When painting a Post cover,” Rockwell stated, “I must tell a complete, self-contained story. An illustration is merely a scene from a story” (quoted in Virginia Mecklenburg, Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, New York, 2010, p. 86).

The impressive sense of naturalism that Rockwell achieved in works from this period including Two Plumbers was achieved in large part through his complex technical process, which he developed and refined throughout the early decades of his career. The 1930s introduced two particularly important changes in his working method. Encouraged by a younger generation of artists that included Steven Dohanos and John Falter, Rockwell began to experiment with photography in 1937. Only after painstakingly collecting the appropriate props, choosing his desired models and scouting the perfect location would photography sessions begin, both on site and in his studio. Rockwell rarely took these photographs himself, preferring to be free to adjust each element while a hired photographer captured images under his direction.

Concurrently, Rockwell also began to rely solely on his friends and neighbors in his new home of Arlington, Vermont, to serve as his models. Living in working-class New Rochelle, New York, had previously required the artist to depend largely on children to serve as models as the majority of the adult population could not spare the long stretches of idle time required to sit for the artist. When he did paint adults, Rockwell employed professional models, a reliance he came to believe hindered the degree of authenticity his work could achieve. However, Rockwell found the opposite in Arlington: a plethora of neighbors of all ages willing to model for him. “Now my pictures grew out of the world around me,” the artist described of this important change, “the everyday life of my neighbors. I don’t fake it anymore” (quoted in Susan E. Meyer, Norman Rockwell’s People, New York, 1981, p. 64).

Two of Rockwell’s studio assistants, Don Winslow and Gene Pelham, modeled for the central characters in the present work, posed in front of a dressing table owned by Mary Rockwell, the artist’s wife (Fig. 3). The artist recognized the benefits that came from utilizing the camera, particularly when his composition included an animal. Images of animals appear frequently throughout Rockwell’s body of work, as the artist often utilized them to visually reinforce his message and tone. In 1954’s Breaking Home Ties, for example, the inclusion of the family collie reinforces the tenderness of this scene of a young man saying goodbye to his hometown and childhood (Fig. 4). Indeed, Rockwell never added an animal to a composition merely to add to its popular appeal. “It takes much kindness and patience to handle animal models,” he once explained, “but the effort is worthwhile because they are so often important elements in story telling pictures…. I do not like to see an appealing animal put into a picture just to save a job. This trick does not fool anyone. I never include an animal in any picture unless it seems natural for it to be in the setting. But when you have a scene in which animals might be expected to appear, paint them well and put them in because people love to see them” (Rockwell on Rockwell: How I Make a Picture, New York, 1979, p. 108) (Fig. 5).

Indeed, the apparent veracity captured in Two Plumbers belies the careful deliberation with which Rockwell executed this and all of his most successful works. The artist’s perfectionism was infamous; he included every element to serve a specific purpose and often created numerous sketches and studies before executing the final version of the painting (Fig. 2). In Two Plumbers, the dog at the lower right serves as an important compositional device. Like many of the supporting players in the artist’s most complex paintings, the dog represents, “a character within the painting’s space whose response to the action we may take as a cue to our own response and through whose eyes we are presumed to see the scene portrayed in its optimum configuration” (Dave Hickey, “The Kids Are Alright: After the Prom,” Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, New York, 1999, p. 119). As Hickey notes, the addition of the dog references a technique of 18th century French painting as exemplified by Jean Honoré Fragonard’s, The Swing, in which the man lounging in the bushes has a revealing view of the swinging woman that the viewer is not granted, yet we know from his expression and reaction that the artist intended for the tone of the work to be humorous (Fig. 6). In Two Plumbers, the worried eyes of the Pekingese underscore the idea that the men are trespassing, which in turn makes us as the viewers complicit in the affair as we watch and laugh but do nothing to stop them.

Rockwell enjoyed referencing other well-known works of art in his own paintings, as it provided the type of visual game that the artist loved to present to his viewers. Rockwell also used these allusions to demonstrate his deep knowledge of art historical precedents. In Two Plumbers, the central figures form an inverted triangle, mimicking a pictorial configuration often employed by the painters of the Italian Renaissance and creating the impression of stability within the composition. The strong horizontality of the window blinds and baseboard is countered by the verticality of the figures, creating a geometric grid onto which Rockwell could add the ornate details of the extravagantly decorated room without sacrificing the harmonious compositional balance of the scene.

The enduring popularity of images like Two Plumbers speaks to Rockwell’s ability to select subjects that appealed almost universally to American audiences, and to uniquely infuse his compositions with compelling elements of comedy. “It is easy to see that had he not been a gifted artist,” stated his biographer Christopher Finch, “Norman Rockwell might well have become a successful writer or director for film or television. Situation comedy has been one of the most popular genres in both these mediums, and no one has a better knack for inventing comic situations than Rockwell” (102 Favorite Paintings by Norman Rockwell, New York, 1978, p. 124). Rockwell was fascinated with television, and by the 1950s, he regularly mined the new medium for source material. Nowhere is this clearer than in Two Plumbers, where the humorous adventures of the plumbers seem a direct allusion to the slapstick antics of the comedy team of Laurel and Hardy, who enjoyed the height of their popularity in America during the 1930s and 1940s (Fig. 7).

Rockwell painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post in 1916, and his last in 1963. While he never abandoned the subtly nostalgic and persistently optimistic aesthetic that made him beloved by Americans and his work instantly recognizable as his own, the subjects he addressed changed over time to reflect the country’s evolving cultural, social and political mores. Ultimately, works such as Two Plumbers not only demonstrate Rockwell’s rare gift for storytelling, but also the genius with which he kept a massive and diverse audience engaged for more than half a century.